N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic Acid: Insights and Directions

Historical Development

Scientists have spent decades looking for substances that solve tough chemical problems in labs and industry. Back in the mid-1900s, the demand for stable buffering agents brought N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, often called BES, into the spotlight. This compound quickly found a home in biochemistry when researchers saw how well it maintained pH in living systems. Personal encounters with lab benches littered with half-tested buffers showed just how crucial this molecule became for experiments that couldn't afford swings in acidity. BES landed its spot thanks to researchers who cared less about making history and more about getting cleaner, more reliable data, especially when serum proteins or enzymes were involved.

Product Overview

N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid belongs to the family of Good’s buffers, which are widely known in biochemistry for their low toxicity and stable buffering range. This organic sulfonic acid acts as an effective buffering agent in the near-neutral pH range, usually between 6.4 and 7.8. In my years of working with protein purification, the selection of the right buffer often made or broke the experiment. BES proved to be a steady choice for protocols that required gentle handling of biological materials and reproducibility over long timeframes. Its low affinity for metal ions and minimal reactivity with biological molecules allowed experiments to focus on the reaction being studied, not unpredictable side effects from the buffer itself.

Physical and Chemical Properties

BES is a white crystalline powder. It dissolves easily in water, forming clear, colorless solutions that don’t give off any discernible odor. With a molecular weight around 213.26 g/mol and a melting point that typically ranges near 305°C (with decomposition), this compound doesn’t break down under standard storage conditions. Its acidity dissociation constant (pKa) sits comfortably at 7.1 at 25°C, putting it squarely in the sweet spot for many enzymatic and cellular studies. During a summer in grad school, I saw just how much reliability matters—some buffers shifted pH after sitting for weeks. BES stuck to its guns, proving stable after each round of tests. This made it easier for new lab members to step into ongoing projects without reworking the basics.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Suppliers usually set minimum purity at 99%, free from heavy metals and with tightly controlled ash content. Specific labeling typically lists CAS number 10191-18-1, molecular formula (C6H15NO5S), and quality certifications such as ISO or USP standards, depending on the application. In practice, reading the fine print on certificates of analysis often means spotting traces of chloride or sulfate that could mess with sensitive experiments. Any reputable chemical supplier is keen to document batch testing and traceability, making sure that when you tear open a new bottle, you know exactly what’s inside. In regulated settings, proper labeling protects both workers and experiments from preventable errors.

Preparation Method

Production of BES typically starts with the reaction of ethylene oxide with monoethanolamine, followed by sulfonation with agents such as sulfur trioxide or chlorosulfonic acid. These reactions require careful control of temperature and pressure to drive selectivity and yield. Small variations during the process—something I learned by shadowing chemical engineers—can produce side products that reduce performance in downstream applications. After synthesis, the crude product undergoes purification steps like recrystallization or ion-exchange, which separates BES from color bodies and residual inorganic materials. Final drying and milling result in a product that flows smoothly, ready for precise measurement.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

Beyond buffering, BES serves as a precursor for several chemical transformations. Chemists use it to introduce sulfonate groups into other molecules or as a protective agent for amino groups during peptide synthesis. The hydroxyl groups allow for straightforward modifications—attachment of fluorescent labels or isotopic tags isn’t rocket science when you’ve done it once or twice. Some industrial syntheses rely on the unique electron-withdrawing effects of the sulfonate, tuning reactivity in multistep reactions. In my lab days, modifying BES often looked like an exercise in patience, since side reactions could eat away at yield unless conditions were spot-on.

Synonyms and Product Names

BES goes by several names in catalogs and literature—N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)taurine, N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid, and the abbreviated "BES buffer." These aliases can confuse even seasoned scientists reading across disciplines, especially if translations drop a descriptor or two. Companies market BES under trade names, often pairing “buffer” with “Good’s” to signal its place among tried-and-true biochemicals. In every stockroom I’ve worked in, chemical safety sheets listed at least three product names, but the CAS number always cut through the noise.

Safety and Operational Standards

Handling BES safely means respecting general rules of laboratory hygiene: gloves, goggles, and working in well-ventilated spaces. Accidental exposure typically doesn’t lead to major toxicity, but even “low hazard” chemicals can cause skin or eye irritation. Many labs store BES in cool, dry areas and keep it away from strong acids and bases. Waste disposal routes depend on local regulations—my first safety training drilled home that every drain has a story, and ignoring chemical compatibility risks fines and real environmental harm. MSDS sheets recommend standard containment and cleanup procedures for spills, underlining the importance of personal and environmental safety. Routine audits and training keep these standards from slipping into afterthoughts.

Application Area

BES sees wide use in biological and biochemical research. It stabilizes pH during electrophoresis, cell culture, and enzyme kinetics. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, it provides a controlled environment for sensitive processes. The low reactivity shines during protein and nucleic acid extraction, preventing unwanted modifications that could skew research or clinical results. Diagnostic industries lean on BES for consistency, especially in test kits where variable pH could mean false positives or negatives. My experiences running diagnostic samples taught me the relief that comes from buffer systems that just work, session after session. Some water treatment plants examine BES and similar buffers for potential to stabilize industrial discharge without crossing safety thresholds.

Research and Development

Innovation continues as researchers engineer new derivatives and blends targeting specific experimental needs. Modifications aim for even tighter pH control, reduced interaction with metal ions, or improved solubility in organic/aqueous mixtures. Government-funded projects track interactions between BES and emerging therapeutic proteins, while private firms tweak the molecule for compatibility with novel diagnostic devices. These efforts come straight from the needs of bench scientists, not management, and the payoff lands in smoother, more reproducible results. Journals and patent filings fill up with ideas that could extend BES utility beyond classic lab environments.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity data positions BES as relatively safe, especially compared to early generations of acid-based buffers that leached heavy metals or produced dangerous byproducts. Animal studies report minimal acute toxicity, with no major adverse outcomes at typically used concentrations. Standard testing covers skin, eye, and inhalation hazards, and chronic studies look for subtle effects over weeks or months. One thing I learned the hard way: assumptions about safety don’t substitute for verified data. Reviews still call for vigilance, especially when increasing buffer volumes in largescale fermentation or manufacturing. Environmental studies flag the need for controlled disposal—breakdown in municipal systems may form sulfonated metabolites with unknown impacts.

Future Prospects

Trends in synthetic biology, diagnostics, and green chemistry continue to drive interest in BES and its engineered cousins. Labs demand buffers that can hold their own during extreme temperature swings, tolerate trace contaminants, and lower environmental footprints. Chemists tinker with new synthesis routes, aiming for reduced byproducts and greener solvents. Collaboration between academic labs and industry partners remains the fastest path to breakthroughs—something I’ve seen first-hand as pilot projects turn into published protocols and commercial products. The direction for BES runs alongside broader industry movements: prioritize safety, enable complexity in research, and answer emerging questions before they turn urgent. Investments in toxicity research, scale-up processes, and smarter blends will likely decide whether BES keeps its top billing a decade from now.

Steady Balance: Why Laboratories Choose BES

BES usually flies under the radar in day-to-day conversation, but for research scientists and biologists, it steps onto the main stage. This buffering agent keeps the pH level steady during experiments, a job that gets more important as labs push for better, reliable results. In simple terms, BES helps researchers avoid angry data. Fluctuating pH can send costly experiments off track. Imagine working on a months-long enzyme study, only to have surprise pH swings sink the results. BES, with its reliable buffering range near physiological pH (6.4-7.8), helps dodge this headache, particularly in biochemical and molecular biology applications.

Real-World Impact: In the Lab and Beyond

One experience stands out from my time in a university lab. Our team spent weeks trying to clone an enzyme. Traces of unwanted acid kept creeping in from the growth medium, and our data was all over the place. Once we swapped in BES, things smoothed out. Growth media, cell cultures, enzyme assays — the results lined up predictably. It doesn’t get much more concrete than seeing consistent data roll in just by making a small change in buffer.

The thing many folks outside the lab don’t notice is how foundational these small chemicals can be. Whether you’re working with mammalian cells or running a biotech startup, you want to reduce variables and keep experiments reproducible. BES answers that need by resisting chemical activity from outside sources, including trace metals, and by not interfering with enzymes or proteins. That means researchers get a clear look at what they’re really testing, not contamination or reaction noise.

A Cleaner Choice for Sensitive Techniques

Outside classical laboratory research, BES also plays a part in electrophoresis. Those gels you see on crime shows — the ones that separate pieces of DNA — depend on reliable buffers. BES doesn’t add a bunch of background noise, especially when compared to some older buffering chemicals. That leaves gels clearer, bands sharper, results sharper. Labs looking for reduced interference often lean in this direction.

Manufacturers are emphasizing purity for BES today, which means less risk of contamination from heavy metals or other unexpected substances. Recent trends also show scientists looking for chemicals with low toxicity. BES, with its minimal biological effect, lets researchers run sensitive procedures such as protein purification with fewer side concerns.

Sustainability and the Bigger Picture

The science world keeps asking about greener practices and lower waste, and buffers like BES have started coming up in these debates. Production and disposal can contribute to environmental load. Some manufacturers are developing purification techniques that reduce chemical waste or recycle byproducts. More can be done — switching to recyclable packaging or looking for alternative synthesis routes are steps that might help. Regulatory bodies also look at chemicals like BES under environmental health standards, which encourages companies to work cleaner from beginning to end.

Wrapping Up: Why It Matters

BES rarely grabs attention outside scientific circles, yet its impact touches medical diagnostics, biotech innovation, and even the training of young researchers. Keeping experiments steady, giving clearer results, and offering low toxicity make it a trustable tool. For all the shiny new tech in laboratories, sometimes it's the dependable supporting players like BES that keep the science honest.

The Building Blocks of a Useful Chemical

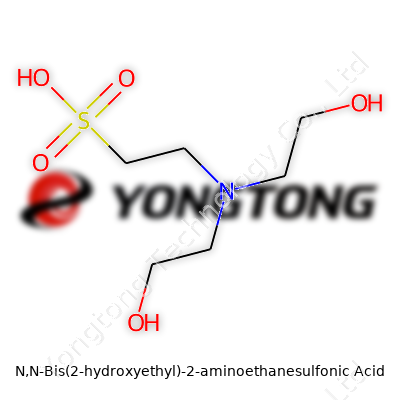

N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid has grown into a staple for many researchers and lab workers, especially in biological studies. Known to many as BES, this compound plays a role in keeping pH stable for experiments and solutions where precision counts. The real appeal comes from its structure: BES contains both sulfonic acid and amine groups, along with two hydroxyethyl side chains. The molecular formula captures this chemical detail: C6H15NO5S.

Description at the Molecular Level

The BES molecule brings together a central ethane backbone with one sulfonic acid (-SO3H) at position 2, and the nitrogen at position 2 connects to two hydroxyethyl groups. Picturing the structure, imagine the core of ethane, where one carbon links up to a sulfonic acid, the second carbon to a nitrogen, which then branches off to two hydroxyethyl arms. These hydroxyethyl groups each have a –CH2CH2OH tail, letting BES dissolve easily in water and interact with other molecules.

A simplified look at the structure:

- The main chain has two carbons connected in a row.

- One end shows the sulfonic acid group (-SO3H), making the molecule an acid in water.

- The nitrogen sits on the second carbon, doubling as a hinge for the two hydroxyethyl arms.

Why Structure Matters in the Lab

Anyone who’s worked with cell cultures or biochemical reactions knows pH swings can throw weeks of work in the trash. BES offers steady buffering between pH 6.4 and 7.8. That dependable buffering comes straight from its backbone—the sulfonic acid can lose protons without letting the solution go wild, and the hydroxyethyl groups hold water closely, supporting clear, unreactive mixes.

Some buffers carry charges that mess with enzymes or cell walls, but BES keeps a neutral profile for most reactions at physiological pH. Its solubility reflects the work of the hydroxyl groups, which keep solutions clear and easy to filter. Flexible, soluble, and chemically gentle, BES helps reproduce experiment results, supporting everything from protein purification to cell imaging.

Concerns and Responsible Use

Laboratories move a lot of buffers down the drain. BES shows low toxicity in standard concentrations, yet anything used by the gram deserves a double-take before it hits the wastewater. Municipal water treatment facilities often lack technology to efficiently remove certain chemical buffers like BES from the waste stream. That gap means everyone in the research community should pay attention to proper neutralization and waste protocols.

Some labs now collect buffer waste for specialized disposal or use methods that neutralize the acid function without sending strong organics into public systems. Ongoing research into replacing sulfonic acid-based buffers with biodegradable options still lags, since the stability and inertness of BES aren’t easy to match.

Applications and the Road Forward

BES stands as a trustworthy buffer for anyone needing error-proof pH control in vitro. The chemical structure—anchored by strong sulfonic acid, hydrophilic hydroxyls, and a simple amine—delivers performance in medical, agricultural, and industrial settings. Reducing risks depends on careful handling, more sustainable alternatives, and continued transparency about disposal methods. Researchers and lab techs who treat BES with the attention it deserves keep science safer and results sharper for the next wave of experiments.

Storage Choices Shape Safety

Working in a lab or around chemicals puts responsibility front and center. Everyday decisions, such as where a bottle sits and how tightly it’s closed, make a difference in workplace safety and product stability. If your compound reacts quickly to light or heat, skipping careful storage can spark a chain of mishaps: spoiled material, risky vapors, or even fire. Most researchers start to notice the impact of small lapses early. Once, I had a vial degrade after one warm weekend, and since then, I always respect those temperature limits.

Choosing the Right Conditions

Every compound reacts to its environment in a unique way. Let’s talk about some basics: Dry, cool, and dark storage spaces usually help prevent the breakdown of chemicals that break down under heat or light. Organic solvents and many pharmaceuticals stay stable at room temperature if kept away from direct sunlight and strong oxidizers. For something labeled volatile or flammable, a well-ventilated cabinet, preferably with fire protection, stops vapors from building up or igniting.

Humidity matters more than many realize. Silica gel or dedicated desiccators soak up stray moisture, which keeps powders from clumping or turning useless. Some salts suck water right out of the air. Others give off fumes that spread if lids get left loose, so sealing containers after each use is not a suggestion, it’s essential.

Handling Protects More Than Just Product

Gloves and eye protection do more than follow protocol. Chemical residue lingers on lids, containers, or pipettes, and it’s easy to forget. Stories from my early days include more than one minor hand burn because I thought a bottle’s rim looked clean enough. If spills happen, absorb with appropriate material and label everything after clean-up. Clear labeling — including date received and opened — saves everyone down the line from confusion or accidental mixing.

Measuring and transferring should stay away from strong air currents or wide-open spaces. Hood work limits exposure to vapors or dust. For toxic or easily oxidized materials, small batch handling limits the scale of mistakes. Waste should move quickly to a marked, secure bin rather than sitting on a bench all day.

Regulatory Benchmarks Matter

Local and federal guidelines matter just as much as manufacturer tips. Agencies like OSHA and the EPA provide detailed rules about flammables, toxics, and corrosives. Following these is a smart move — fines and shutdowns are real risks for those labs that cut corners. If you’re storing in bulk, even more layers kick in — ventilation, restricted access, spill containment areas.

Regular checks on shelf life and inventory reduce surprises. Outdated material sometimes looks no different than fresh, but its properties change. Assigning one person to track expiry and disposal avoids confusion. Getting lazy about this can lead to dangerous reactions or waste of funds.

Improving Everyday Practice

Training, reminders, and sharing near-miss stories build a culture where everyone watches not just their own bench, but their neighbor’s too. Even minor improvements — keeping storage maps up to date, reviewing safety data sheets each month — reinforce smart habits that prevent accidents. Tech can help, but nothing replaces a team that looks out for each other and respects the material they work with.

Let’s Talk About This Chemical

Researchers and lab workers might recognize N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid by its common short name: BES. This buffer solution shows up regularly in the fields of biochemistry and molecular biology. Some people hear “lab chemical” and immediately worry about risks. My own early days volunteering in a research setting drilled into me the importance of checking a chemical’s safety data sheet before even opening its container. So, what’s the truth here—should people worry about handling BES in labs, teaching environments, or even large-scale research?

Understanding the Hazards

Looking up BES in reputable safety databases like PubChem or NIOSH shows that it lands in a low-to-moderate risk category compared to strong acids, solvents, or industrial cleaning agents. Skin and eye contact might cause some irritation. Ingesting BES is not recommended (just like pretty much every lab chemical), but the substance does not register as acutely toxic in available animal studies. That’s a relief, but personal protective equipment remains a smart choice. Think gloves, goggles, and lab coats rather than full hazmat suits.

Accidental Spills and Exposure

I remember an awkward spill once during a rushed experiment—not with BES, but a similar buffer compound. Cleaning the mess meant tossing disposable gloves, washing hands thoroughly, and wiping surfaces with damp towels. These emergency protocols are simple but effective for many lab-grade buffers. With BES, good ventilation, quick cleanup, and routine handwashing generally prevent bigger issues. Data shows BES doesn’t produce toxic fumes at room temperature, so breathing hazards rarely come into play.

Long-Term Effects: What Does the Science Say?

There isn’t much evidence to show long-lasting poison or chronic health impact from BES. Some chemical buffers break down over time to form less desirable byproducts, but BES doesn’t stack up as a major threat. Environmental agencies haven’t flagged it for persistence, bioaccumulation, or cancer suspicion. A good practice, which I learned from an old chemistry professor, is to store unused solutions sealed and label everything—even with low-toxicity compounds. This isn’t just bureaucracy; it actually helps track accidental exposure and waste.

Waste Disposal and Environmental Concerns

Modern research labs often struggle to keep up with disposal regulations. People want their science to matter, but nobody wants to pollute groundwater or harm wildlife. BES, by its chemical nature, seems unlikely to cause major environmental havoc. Still, flushing large amounts down the drain is a bad look. Many labs funnel used BES solutions into hazardous waste streams so treatment plants can process them responsibly. Some cities have special chemical amnesty days and lab techs sometimes gather old bottles for a single coordinated drop-off.

Realistic Safety Habits

The main lesson from years in science is to treat every unfamiliar chemical with respect even if the label downplays danger. Reading MSDS documents does not sound thrilling but always turns up useful tidbits. With BES, minimal hazards mean most risk comes from sloppy habits or not paying attention during experiments. Most people will never need a panic button while using it, but basic gear and attention make all the difference. Workplace safety depends on constant review of protocols, and it never hurts to tailor policies to actual chemical risks, not just rumors or fear.

Getting Real About Chemical Purity

Most people talk about purity as a percentage—99%, 98.5%, maybe 95%. In the lab, you get used to reading labels searching for those numbers, figuring out if the material suits the task. Purity means more than just a number on a label, though. For a researcher, there’s no substitute for handling the real product, opening the container, and testing it yourself. Numbers speak, but the consistency of the powder or size of the crystals also says plenty about what you’re dealing with.

Companies usually provide analytical data—high-performance liquid chromatography, melting point, elemental analysis. Even seasoned chemists rely on third-party verification, double-checking batches with their own equipment. Trust comes from experience and independent checks, not just the paperwork packed in the box. Too many times, a “>99%” compound ends up needing purification before you can actually use it.

The Physical Form: Why It Matters

Opening a bottle expecting a free-flowing powder and instead finding sticky clumps always throws a wrench in your day. Powders, granules, flakes—most suppliers settle on powders simply because they transport easily and measure out quickly in a lab. Granules sometimes feel easier to handle, but powders dissolve faster when working with solutions. Flakes show up every now and then, especially for certain organics, and sometimes they prove challenging during transfer.

Handling the product as supplied makes all the difference. Fine powder gets airborne, making some folks reach for masks and gloves. Clumped or hygroscopic materials signal moisture in the room, reminding you to work quickly or under a nitrogen blanket. Companies add desiccants for a reason; a careless storage room can knock purity down before you even run your first experiment. It all comes down to understanding what’s in the jar and adjusting your habits for each batch.

Putting Purity to the Test

Anyone who has worked in manufacturing or academic labs knows that getting a number on a label doesn’t guarantee performance. Simple tests—solubility, color change, melting point—reveal what a certificate can miss. High-purity claims sound great until leftovers from synthesis shift your reactions. Even small traces of water in a “dry” chemical like sodium acetate can trip up a sensitive process. Maybe you put faith in a single lot for repeat experiments, only to find later batches act different. The difference between 98% and 99% purity often determines whether your project ends in success or frustration.

Buying in small batches or requesting detailed batch analyses keeps surprises to a minimum. A reputable supplier earns trust batch after batch. If something feels wrong, it’s up to you to pick up the phone and ask, or better yet, get an extra sample from another supplier. Most serious chemistry work means keeping unexpected variables out of the mix.

Better Solutions For Buyers and Sellers

Improving transparency tops the list. Batch-specific data instead of generalized purity ranges helps buyers pick what they need. Suppliers who encourage feedback or provide open lines for questions build lasting relationships with labs and manufacturers. Sometimes a quick phone call with a technical expert solves problems before they hit production.

As industries demand higher purity, and research gets ever more complex, both buyers and suppliers need to keep dialogue going. Clear data, honest communication, and consistent product handling beat any glossy label or fancy packaging. In the end, purity and form together decide how work gets done—and whether research runs smoothly or struggles against the unexpected.