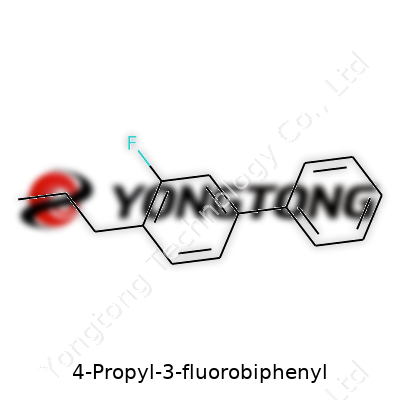

4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl: Real-World Perspective and Emerging Insights

Historical Development

Back in the early days of synthetic organic chemistry, biphenyl compounds earned respect for their versatility in both industrial and laboratory settings. As the field matured, adding different substituents to the biphenyl backbone—propyl, fluorine, methyl, and so on—opened up a toolbox for chemists looking to fine-tune chemical functionalities. In the late 20th century, serious attention landed on halogen-substituted biphenyls for their stability, electronic properties, and emerging roles in the pharmaceutical and materials science sectors. The introduction of a fluorine atom tends to change electron density in a way that can transform biological activity or adjust thermal properties, while the propyl group alters solubility and reactivity, a recipe that’s kept 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl relevant in research and industrial application.

Product Overview

This molecule stands out as a member of the halogenated biphenyls, with a propyl group at one end and a fluorine at the other—a structure that shapes both its reactivity and its niche uses. I’ve found chemists appreciate its dual nature: the molecule carries the hydrophobic character of propyl alongside the distinctive, electron-withdrawing punch of a single fluorine. Its precise structure means it doesn’t just blend into the background in a compound library; in research circles, it draws attention for modifications and structure-activity investigations, particularly when precise tuning of molecular features affects bioavailability or materials applications.

Physical and Chemical Properties

You might find 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl described as a colorless to pale oily liquid under standard conditions, with a distinct lack of odor and a density falling between 1.03 and 1.12 g/cm3. The melting point usually sits below room temperature, making it a liquid for most storage needs. Its boiling point heads north of 270°C, with low vapor pressure and moderate solubility in organic solvents. Most routine solvents pair well—dichloromethane, ether, toluene—which becomes helpful during workup and analysis. The molecule’s stability owes much to the robustness of the carbon-fluorine bond, offering resistance to oxidative breakdown and adding shelf life to commercial batches.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Most reputable suppliers deliver 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl with purity levels above 98%, often verified by both NMR and HPLC. Labels state batch number, net mass, and manufacturing date, as well as the molecular weight (204.26 g/mol) and specific storage instructions—cool, dry, tightly closed, away from direct sunlight. Full certificates of analysis accompany each shipment, giving researchers peace of mind about both composition and trace impurity content. In the laboratory, glass vials with PTFE-lined caps cut back on sample loss or contamination by reaction with plastics.

Preparation Method

A common route for making this compound starts with a Suzuki coupling—this approach links a propyl-substituted phenylboronic acid with a 3-fluorobromobenzene under palladium catalysis. I’ve run this reaction on the bench using a base like potassium carbonate in toluene, stirring at 80-100°C under nitrogen for twelve hours. Product separation often runs through flash chromatography, followed by solvent evaporation under reduced pressure. Some labs opt for direct fluorination of a preformed biphenyl, but positional selectivity can drop, so Suzuki cross-coupling reigns, especially at scale.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

Chemists keep exploring ways to exploit both the propyl and fluorine positions for further transformation. Nitration, sulfonation, and halogenation typically center on the unsubstituted rings—not always easy, given the electron-withdrawing fluorine. Dehydrohalogenation and Grignard reactions also see some play, especially for attaching new functional groups, building heterocycles, or prepping cross-coupling partners. I’ve seen its structure survive fairly harsh acid and base treatments—owing, again, to the stability that fluorine and the biphenyl skeleton provide.

Synonyms and Product Names

Depending on the supplier or registry, the molecule goes by several names: 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl remains the IUPAC-flavored standard, but you might spot identifiers such as 4-n-Propyl-3-fluoro-1,1’-biphenyl or 3-Fluoro-4-propylbiphenyl when scanning catalogues, scripts, or patents. CAS numbers (such as 1064770-81-3) help avoid confusion if naming conventions are ambiguous, as they often are in multi-national chemical supply chains.

Safety and Operational Standards

Anyone handling halogenated biphenyls treats safety as more than a box to check. The compound may not rate high on acute toxicity, but gloves, goggles, and fume hoods still stay non-negotiable in my workspace. Spills mean absorbing with inert material rather than washing down the drain. Disposal usually goes through licensed chemical waste contractors, not public sewer systems. Chronic inhalation or skin contact risks build up over time, especially in settings without enough ventilation. MSDS sheets spell out handling requirements, emergency procedures, and incompatibilities—paying attention keeps work straightforward and accidents at bay.

Application Area

The reach of 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl stretches across pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and emerging materials. Medicinal chemists use it as a scaffold for SAR (structure–activity relationship) studies or as a non-polar intermediate for drug leads. In the materials world, this compound finds use as a building block for liquid crystals and as a dopant in polymer blends. Performance data keeps fueling research interest for organic electronics due to predictable charge-transfer properties tied to the propyl and fluorine substitutions. Some researchers see value in agricultural chemistry—flavonoid analogs and herbicide candidates have used similar scaffolds.

Research and Development

Laboratories in Asia, Europe, and North America still champion the use of 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl as a reference standard and platform for new molecule synthesis. Fluorinated biphenyls often end up in high-throughput screening libraries, where their subtle changes in polarity and metabolic stability shape how larger compound sets behave. Postdoctoral researchers with experience in medicinal chemistry frequently use such compounds to probe drug metabolism, absorption, and receptor interactions, especially for targets related to CNS activity or metabolic diseases.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology studies so far describe low acute toxicity at routine laboratory concentrations, but broader environmental questions still linger. Structurally, biphenyls have a history as persistent organic pollutants. Even after halogen and alkyl substitutions, breakdown products from incineration or metabolic processes raise concerns. Eye and skin irritation risks appear mild in standard reports, as do short-term inhalation dangers. Regulatory agencies ask for more studies under REACH and similar frameworks, especially as production volumes tick upward and application areas diversify.

Future Prospects

The near future will likely see 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl and its analogs moving into yet-untapped parts of material science and molecular imaging. Automated synthesis technologies now allow for rapid screening of substituted biphenyls, where even slight shifts in substitution pattern alter bulk material characteristics. Environmental chemists face the dual task of charting long-term persistence and breakdown pathways, fueled by advances in analytical instrumentation. Given new possibilities in electronics, sensors, and pharmaceuticals, academic and industrial R&D groups keep a close watch. Encouraging ongoing dialogue among synthetic, analytical, and regulatory experts will anchor safe and responsible use without stunting scientific progress.

Digging Into Its Applications

People often ask about the purpose of 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl. This synthetic chemical doesn’t appear in household goods or food. You won’t find it on drugstore shelves or in cleaning products. Where it actually shows up is in scientific labs and specialized industries where every detail in a molecule matters.

Chemical Research and Material Science

Chemists frequently use this compound as a building block. In pharmaceutical research, 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl helps scientists study how small changes to a molecule can affect its behavior. That’s especially true among researchers designing new drugs to target diseases at a molecular level. By modifying one section of a biphenyl compound—adding a fluorine atom here and a propyl side-chain there—they often see big changes in biological activity. That lesson comes straight from medicinal chemistry: slightly different molecules can trigger very different reactions inside the body. Sometimes a tweak makes a new cancer drug more effective; other times it makes an old pesticide safer for the environment.

Material science also draws on this compound. Engineers and chemists turn to biphenyl derivatives like this when they work on liquid crystals and organic electronic materials. Liquid crystals, like those in your TV or phone, depend on molecules with just the right shape. Adding a fluorine atom changes how the molecules line up with each other, influencing the way an electronic display shows color or brightness. In my own university work, screening dozens of biphenyl derivatives for material science projects, that fluorine atom often meant stronger, more reliable performance under heat or light.

The Pharmaceutical Pipeline

Drug developers need to stay ahead of new challenges—rising resistance, changing disease patterns, high regulatory standards. Compounds like 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl become tools for these challenges. Scientists studying brain disorders, pain, or autoimmune conditions search for candidate molecules that protect healthy cells yet attack disease. A compound nobody cared about last year can quickly become a key intermediate—the piece chemists use to build more complex and promising candidates. Patents reference these kinds of molecules as starting points for anti-inflammatory or anti-cancer leads. That gets fact-checked by laboratories through rigorous tests, including toxicity screens and target binding studies. Academic papers reveal how each modification to the molecular structure changes the way these chemicals interact with biological targets.

Concerns and Responsible Use

Advanced chemicals raise some hard questions. Even if 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl itself isn’t a commercial product, its relatives sometimes turn up in unexpected places like old electronic waste. There’s a long history of biphenyls with industrial uses causing pollution or health problems—think PCBs in river systems. Good research makes all the difference, and regulatory oversight is essential. Safe disposal, monitoring, and tracking new chemicals as they enter industry or the environment keeps everyone out of trouble.

Scientists, companies, and government labs must work together to screen new compounds and flag those the public needs to know about. Finding greener alternatives and sharing environmental impact data helps prevent past mistakes. Progress in chemical safety means sharing not just successes but lessons learned from every misstep. Those commitments make sure the next tool for cancer research—or a new display material—carries more benefit and less risk.

The Building Blocks

Every so often, chemistry gives us a molecule that crops up in research papers, patent filings, and lab discussions. 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl fits that profile. This compound belongs to the biphenyl family—a familiar backbone in medicinal chemistry and materials science. In plain language, biphenyls are two benzene rings joined together by a single bond. The structure invites modification, and people in labs keep swapping out different pieces on the rings to tune properties for everything from liquid crystals to pharmaceutical agents.

Dissecting the Structure

Peeling back the jargon, 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl means the molecule carries two specific groups on its rings. The propyl group, a simple chain of three carbons, attaches to the fourth carbon on one ring. The fluorine atom locks onto the third carbon of the other ring. The layout swings the molecule’s properties in unique ways. If you studied a chemical diagram, you’d see two benzene rings. On one, a propyl chain sticks out: three linked carbons, easy to spot. On the other, a tightly bound fluorine sits, barely noticeable compared to bulkier groups but influential all the same.

Real Impact on Research and Design

These small tweaks—propyl here, fluorine there—change more than just appearance. Substituting fluorine can knock up the stability of a molecule, as the tight bond resists breakdown. Medicinal chemists often put fluorine in a molecule to help it survive in the body, hoping to dodge enzymes that would otherwise chew it up. For materials science, adding or swapping groups can impact melting points, flexibility, and how molecules line up in a solution or a film. With biphenyl backbones, minor changes set the tone for how larger structures behave. This is crucial in the development of liquid crystals for screens, where the alignment of molecules changes how a device displays images.

Lessons from the Lab and Beyond

My own time spent in small organic synthesis labs showed how picky these molecules behave during reactions. Adding a propyl group sounds straightforward, but it makes the ring less reactive, slowing down further changes. When fluorine sneaks in, it often demands stronger conditions or more selective catalysts. I remember hours of TLC plates and chromatograms just to confirm that both the propyl chain and the fluorine atom landed in the right places. It’s not just intellectual curiosity; the commercial side depends on reliable, repeatable syntheses. Patents hinge on these little structural differences.

Tackling Synthesis and Purity

Getting high-purity 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl takes patience. Contaminants show up as side-products, sometimes just isomers with a group slipped to the wrong spot. These trace amounts might be invisible to the naked eye, but they throw off drug tests or muddy the clarity in a display material. High-performance liquid chromatography and NMR help, but they add cost and time. Some chemists look for greener solvents or track down milder catalysts to trim environmental impact, trying to keep labs safer and waste streams lower.

Why This Matters

It’s easy to overlook how crucial small molecular changes become across research and industry. 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl gives us a snapshot—science packed into a scaffold where tiny groups make all the difference. Getting the chemistry right means hitting the mark with new devices, better medicines, and safer processes at scale. Every group added or swapped on a biphenyl flips another switch that shapes our experience with technology and health.

Looking Past the Chemical Name

Some chemicals hardly get a day in the spotlight unless there’s a spill or lab accident. 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl is one of those names that float in dense research circles, and if you aren’t a chemist, it reads more like something you’d rather not touch. A big chunk of the public makes assumptions when a compound sounds synthetic or tough to pronounce. That can mean missing the real risks, or sometimes inflating them far beyond what the science supports.

What We Actually Know

Searches for toxicity data on 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl turn up quiet digital corridors. There’s no established safety profile from heavyweights like the National Institutes of Health or the European Chemicals Agency. It isn’t on lists of common industrial hazards or major environmental risks. That doesn’t mean it’s automatically safe, but it does point to a gap in routine use and, possibly, investigation.

Anyone with working experience in lab safety knows lack of data means you play it safe. If you’re in academia or chemical manufacturing, there’s a rule: if information on hazards isn’t available, you don’t take extra liberties. Gloves and masks come out. Fume hoods get used. No one wants a mysterious rash or headache, even if such reports don’t exist in literature. This compound doesn’t even show up on most chemical suppliers’ safety sheets, which tells a story: rare, specialized, not for broad market use.

Structure Points to Some Possible Risk

Chemically, 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl shares features with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). This doesn’t guarantee similar hazards, but that family history puts up a yellow flag. PCBs made headlines for their toxicity and persistence in nature. Inhaling or ingesting them wrecked people’s health, sometimes after years of slow exposure. Substitutions—like swapping chlorine for fluorine or alternative side chains—change physical behavior and biological uptake, but core principles of chemical caution still apply.

Here’s where lived experience sharpens perspective. Fluorinated aromatics, related by chemical backbone, often survive in environments for years. As a scientist, I’ve watched simple solvents linger in soil around spill sites, unseen but present and uncooperative. Some synthetic organics cause unexpected neurological or liver effects, and it’s rarely immediate. Sometimes companies don’t feel pressure to publish full testing because a compound barely leaves the lab.

Better Safe Than Sorry

Companies and academics could step up and fill the data gaps through systematic screening. Readers may not realize, but there’s an industry trend to run “read-across” studies for rare chemicals: researchers compare the structure with known compounds and run prediction models to flag likely toxicity. Even without direct evidence, companies should make adoption slow and measured. If something behaves like a persistent organic pollutant, treat it with healthy suspicion.

Folks at the Environmental Protection Agency, and similar authorities abroad, could require screening of new biphenyl derivatives for environmental fate and bioaccumulation. Pushing for transparent, peer-reviewed animal testing when introducing these chemicals is responsible risk management. As a worker or neighbor near a facility using these chemicals, demanding open disclosure from management makes sense. If you can’t get a material safety data sheet, ask why.

There’s a reason old-timers in synthetic labs stick to old sayings: “Don’t trust what you can’t pronounce.” If it’s unfamiliar, treat it like the worst-case scenario. Personal protective equipment, proper handling, fume extraction—these aren’t just guidelines, they’re routines built from hard lessons. Even if broad toxicity isn’t proven in public records, chemical respect beats regret every time.

Why Proper Storage Matters

4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl crops up in lab environments where safety is always the top concern. Mishandling can lead to chemical spills or ruined experiments. Even if you’re working with a small sample, careless storage brings headaches. Containers that aren’t tight enough let vapor escape, which not only wastes material but can introduce airborne irritants.

Safe Storage Conditions

I always keep compounds like this in a cool, well-ventilated spot—nothing fancy, just a place away from sunlight and any heat source. It pays to use amber glass bottles with screw-tight lids, which guard against both light and air. Letting sunlight hit fluorinated biphenyls over time can change their structure. Cold doesn’t hurt, either. If a fridge is handy, storing the container there gives extra insurance against decomposition.

I’ve watched chemicals degrade after a few weeks in a warm storeroom, so I don’t risk it, even for shelf-stable materials. Temperature swings speed up chemical changes. Refrigeration slows things down, so product quality lasts through the semester. Every container gets a label with the chemical name, date received, and my initials. This keeps tracking easy if questions pop up later.

Handling Precautions

Gloves, goggles, and a lab coat become routine. You never want something like this on bare skin. It may not seem dangerous on paper, but a little spill can irritate right away, especially if splashed in your eyes. I keep a spill kit close—paper towels, absorbent powder, and a sealable bag for clean-up. A friend once tried moving bottles without gloves “just for a second” and spent the afternoon rinsing her hands after a splash.

Work inside a fume hood. Even low-toxicity chemicals can create vapors that you’d rather not inhale, especially with biphenyl structures. Nose and throat irritation doesn’t take a big dose. No one enjoys headaches from working with bad air, so the hood isn’t optional in my book.

Limiting Contamination

I use spatulas and pipettes that never see other chemicals. Cross-contamination wastes material and can ruin results. I toss disposable pipette tips or wash glassware right after use—otherwise, traces of 4-propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl get where you least expect. Shared containers always cause confusion, so every bottle stays with one person or team.

Sharing a plate or unfinished cup of coffee on the lab bench is off-limits. Anything spilling means the risk goes up. Keeping snacks and drinks away from chemicals protects everyone, even on busy days.

Disposal and Emergency Preparedness

Leftover solutions never go down the drain. My campus chemical waste procedure calls for double-bagging and sealing containers, then putting them in a dedicated chemical waste bin. Even a small amount can cause trouble for water treatment if released down the sink. Eye wash stations and safety showers are checked every week; no one wants to search for the right equipment during a spill.

Team training and regular safety refreshers keep habits sharp. Reading the latest chemical safety sheets helps me stay prepared. There’s no downside to staying ahead on lab safety, especially with organic compounds like 4-propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl.

Chemicals and Access: Safety and Responsibility Above All

People searching for 4-Propyl-3-fluorobiphenyl often have a purpose in mind, whether that’s lab research, commercial development, or a curiosity sparked by recent science articles. This compound turns up in organic synthesis and some advanced materials research. Yet most of us—unless we’re trained chemists—never hear about it. The question about where to buy a niche compound like this brings up more than a simple shopping list. It cuts straight to issues of safety, regulation, and trust in science.

Standing With Science: Proper Sourcing Over Shortcuts

My own experience has shown that cutting corners on where or how you buy specialty chemicals creates lasting problems. Reliable results demand legitimate sources. Most countries regulate the sale of chemicals not only to stop criminal misuse, but also to prevent untrained people from facing exposure risks. Marketplace websites and unverified suppliers might promise quick shipping, but their standards can’t compare to certified distributors. Established suppliers require identification, often request proof of professional credentials, and trace orders to protect both public health and their business reputations.

Staying In Control: The Risks Behind Unregulated Sources

Unverified online sellers have flooded social media and ecommerce platforms with chemical compounds. I saw cases in graduate school where students tried these avenues—unlabeled bottles, missing safety sheets, pigments where a pure compound should appear. Labs and classrooms quickly turned into hazards. Reports show a spike in chemical mishaps and scams traced back to gray-market sourcing, not to mention the environmental mess from improper shipping or disposal.

Building Trustworthy Supply Chains

Ethical supply chains protect not only buyers, but also workers and communities. Several international laws push for traceability: REACH in the EU, TSCA in the United States, along with lists from national drug enforcement agencies. Licensed vendors walk buyers through paperwork and provide safety instructions. While this process takes extra effort, it shields everyone from risks—fire, toxic contamination, legal trouble.

The Value of Specialized Chemical Distributors

Distributors earn their place in the research community by maintaining transparency and accountability. Companies serving universities, hospitals, and industrial labs invest in documentation and third-party audits. I’ve watched researchers discover fraudulent reagents that wiped out months of work, only to realize that their suppliers cut corners with storage or mislabeling, violating both ethics and law. Using reputable suppliers means gaining access to analytical data, correct CAS numbers, and technical help when things go wrong.

Wider Impacts and the Path Forward

Science drives progress, but only if trust and safety keep pace. Opening up chemical distribution without checks could lead to drug abuse, environmental harm, and injuries across the board. People serious about research should support efforts by regulators, scientists, and companies to keep these compounds accessible to qualified users—but out of the hands of those chasing shortcuts or profits. Responsible channels, up-to-date training, and a culture of safety keep both science and society strong.