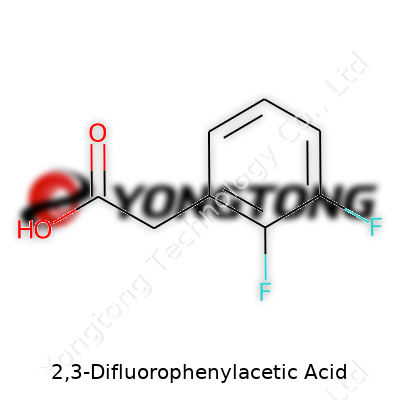

2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid: A Closer Look

Historical Development

Chemists have worked with fluorinated aromatics since the early 1900s, driven by the search for new molecules in pharmaceuticals and agriculture. 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid emerged out of the larger movement to introduce fluoro groups into phenyl structures, hoping to increase bioactivity and stability. In the late twentieth century, researchers began paying attention to the unique properties fluorine offers—its strong electronegativity and small size altered reactivity and metabolic pathways. This molecule grew in appeal as labs in Europe and Asia developed more refined synthesis routes, making it accessible for large-scale application. As the knowledge base expanded, its uses proliferated in pharmaceuticals, crop protection, and materials science.

Product Overview

This compound, with its two fluorine atoms on the phenyl ring adjacent to the acetic acid side chain, carries a lot of strategic interest. The combination of a carboxylic acid group and aromatic fluorines gives useful characteristics. Labs and manufacturers look for it in solid form, typically as a white to off-white powder, known for stability under normal storage. Its importance traces back to the fluoro-arene trend—an approach that makes biologically active molecules last longer in the body or in the environment.

Physical & Chemical Properties

2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid has a formula of C8H6F2O2, with a molecular weight around 172.13 g/mol. Solubility favors common organic solvents—ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, and methanol do the trick—while it struggles a bit in water. The melting point falls roughly in the 84-89°C range, which keeps it solid at room temperature but not too tough to handle in the lab. The acid group adds a clear sour, slightly puckering scent, while the fluorines boost its chemical persistence and lower reactivity of the ring against oxidation.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Industry standards for 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid ask for purity above 98%, typically confirmed by HPLC, NMR, and mass spectrometry. Common labels will include molecular formula, purity, lot number, batch date, storage conditions (keep sealed, cool, and dry), and handling directions to meet good laboratory practice. The product ships in tightly sealed containers, often amber glass or special polyethylene bottles, to protect against light and moisture.

Preparation Method

Most synthetic chemists follow a few practical approaches: one involves using a fluorinated benzene derivative as a starting point and then installing the acetic acid group through a Friedel–Crafts acylation, followed by a reduction step and then carboxylation. Others favor Suzuki coupling to piece the skeleton together, attaching fluoro-phenyl boronic acids to appropriate partners. The choice boils down to cost, availability of raw materials, waste management, and throughput. These methods balance heat, solvent choices, catalyst selection, and work-up steps to keep yields high, by-products low.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The electron-withdrawing nature of those fluorines changes how the aromatic ring behaves. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution becomes more feasible, especially in the ortho and para positions to the acid. The carboxyl group joins in to make esters, amides, and acid chlorides with standard organic techniques. In pharmaceutical research, chemists swap the acid with amino or hydroxy groups to build new drug candidates. The stable framework lets researchers attach other groups without risking ring degradation—a big deal in lead optimization.

Synonyms & Product Names

In the chemical market, you might find it listed under names such as 2,3-DFPAA, o,p-difluorophenylacetic acid, or by catalog numbers from different suppliers. The systematic name is 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid. Academic papers sometimes shorten it to DFPA. Awareness of synonyms matters, especially in supply chain and regulatory settings, to avoid confusion and ensure accurate procurement.

Safety & Operational Standards

Workplace safety plays a central role in handling this acid, as with all fluorinated organics. Material safety data sheets (MSDS) cover eye and skin contact risks—itchiness and mild irritation can develop. Well-designed labs work with gloves and eye protection, fume hoods blanket the area, and spills get neutralized quickly, usually with bicarbonate solutions. Waste streams must get treated as halogenated organics, collected in separate drums for professional disposal. Regulatory compliance covers GHS labeling, and European REACH standards already evaluate it due to the presence of fluorine—a concern for long-term environmental impact.

Application Area

Researchers in drug development and agrochemicals lead the demand, using this acid as a building block for more complex molecules. The presence of fluorines helps block enzymatic degradation, a trick favored in drug design to increase half-life and avoid rapid breakdown in the liver. Crop scientists look for this stability to extend the window of pesticide action. Some material scientists work with derivatives to tweak polymer backbone properties, seeking thermal or chemical resistance improvements that only fluorine substitutions provide.

Research & Development

R&D efforts focus on expanding the toolbox around 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid. Papers track alterations in biological activity—subtle shifts in substitution patterns can swing activity from antifungal to anti-inflammatory. Early-stage clinical candidates have sprouted from this scaffold, hinting at future pharmaceuticals. Chemists keep looking for greener syntheses, aiming to replace traditional halogenation and coupling steps with catalytic or electrochemical methods to cut waste. Collaboration between academia and CROs guides optimization, with high-throughput screening speeding up the hunt for new leads.

Toxicity Research

Toxicological studies on this molecule and close analogs study bioaccumulation, liver effects, and breakdown rates. In rat models, acute toxicity stays modest at levels relevant to laboratory exposure, though chronic tests point to the need for monitoring. The fluorine atoms, while boosting bioactivity, raise red flags about persistent environmental traces. Ecotoxicity screens show low breakdown in soil and water, so regulators track these compounds closely. Personal experience in the laboratory highlights the need to keep exposures below established TLVs and to use engineering controls for tasks involving substantial quantities.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid will stick around as a staple in the chemist’s toolbox, especially for researchers hunting for new drug candidates or crop protection agents with improved lifespans. Startups in green chemistry study how to recycle or break down persistent fluorinated organics, potentially turning this challenge into a competitive edge. Advances in catalysis and bio-based fluorination might reshape the cost and availability of this acid and its relatives. As research expands, scientists exploring structure-activity relationships will keep returning to this scaffold, knowing its track record and untapped potential in a range of industries.

Digging Into Specialty Chemistry

Mention chemistry, and most people think about bubbling beakers or perhaps the medicines that line pharmacy shelves. Few folks outside labs would have heard of 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid, yet its footprint runs quietly through corners of the pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries. I spent years collaborating with researchers who handle intermediates like this, so I have a sense of their everyday reality: carefully connecting building blocks, tracking batches, and troubleshooting supply issues that spill into bigger challenges downstream.

Ingredient With a Purpose

In essence, 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid plays the role of a building block—a starting point for more complex molecules. Chemists use it because the fluorine atoms in its ring change how reactions unfold, making it possible to create products with improved activity and stability. Drug developers feel this at the bench. A simple switch on a ring can bump up a medication’s efficiency or keep it from breaking down too soon in the body. That matters—especially for tough diseases where standard treatments fall short or bring along too many side effects.

Pharmaceutical companies look for molecules with the right traits. Adding a difluoro group in just the right spot, as with this acid, nudges properties such as metabolic resistance and how easily a compound dissolves. I’ve watched teams pour over structure-activity relationships and compare how tweaks in an aromatic ring shift results in an animal model. A small change on paper can keep a program moving forward, or save years of research spent chasing a dead end.

Reaching Beyond Medicines

The story does not end with medicine. Fluorinated compounds are common in agrochemical development—specifically in herbicides and fungicides. Plants’ enzymes often can’t break down these compounds easily, which helps farmers manage pests and disease with fewer applications. Here too, the choices chemists make with precursors like 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid ripple outward, impacting yield, cost, and sometimes even the regulatory environment when persistent chemicals accumulate. My conversations with growers and crop scientists make it clear—what happens in the lab shows up in the field, sometimes years later.

Challenges on the Path

Complexity brings hurdles. Sourcing specialty reagents like this one can get dicey, and inconsistent quality causes headaches during scale-up. I remember projects dragged down by purity or documentation hiccups. Extra costs and longer timelines can follow. Stringent controls become essential, both to keep chemists safe and to line up with environmental safety rules. Fluorinated waste streams need careful handling because of their persistence and potential toxicity.

Smaller manufacturers sometimes run lean on quality management, which makes picking a supplier fraught with risk. A company with ISO certification and transparent batch records stands out. Regulatory shifts like the push for green chemistry and PFAS restrictions also color decisions. Some innovators now explore less hazardous fluorination methods or alternatives that get the job done with less risk for people and the planet.

Moving Toward Solutions

Better access to reliable information helps developers avoid pitfalls. Coordinated action from chemists, procurement teams, and regulators supports responsible use from lab to large scale. Investments in greener synthesis routes can ease environmental burdens while opening up new products.

Looking back, each step with a specialty intermediate like 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid involves a web of choices. Those working in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and specialty chemicals bear the weight of those choices—but they also see the impact, whether as safer drugs, bigger harvests, or less hazardous waste.

Understanding the Risks and Priorities

2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid looks like many other fine white powders common in chemical inventory rooms. Still, storage isn’t as simple as tossing it on a shelf. From years of handling specialty chemicals, I know a casual approach invites mishaps, wasted research time, and sometimes real health hazards. These compounds reflect decades of careful development; respecting them protects research, people, and the environment.

Keeping It Dry and Cool

Moisture ruins the stability of many carboxylic acid derivatives, and 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid counts itself among them. A dry, well-sealed container matters. Humidity creeps in—even through careless cap closures. Keeping the container screwed shut and using a silica gel pack in the cabinet or inside the storage jar adds a simple layer of protection.

Temperature swings wreck the consistency of most organic compounds, so storing it at room temperature—roughly 20–25 degrees Celsius—makes sense. High humidity or direct sunlight accelerates degradation. Years of experience tell me that a dark, cool cupboard, well away from heat sources like sunny windows or radiator pipes, is worth the extra steps. Some lean on refrigerators, but unless the datasheet specifically rules it out, room temperature storage avoids issues with condensation and frost buildup ruining seals.

Storing Away from Hazardous Companions

Acids and bases fight when given the chance, even in vapors. Never cram 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid next to strong bases, oxidizers, or reducing agents. Mixing up chemicals because of poor labeling or crowding remains one of the silent causes of lab incidents. Years in shared research spaces have taught me this caution comes not out of paranoia, but out of respect for unpredictable reactions and for everyone passing through the lab.

Each bottle needs a clear label. Writing the opening date with a permanent marker on the container’s label helps track shelf life. Cross-contamination ruins pure materials and experiments, so always use clean scoops or spatulas—never reuse tools between bottles.

Ventilation and Protective Measures

Breathing fine powders, especially aromatic acids, gets risky over time. In my graduate years, even the minor irritants built up after months of regular exposure. Always store and weigh 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid inside a chemical fume hood if possible. Escaping dust lingers in still air, so allow space for the bottle and tools, and keep the work area tidy to avoid accidental spills.

Nitrile gloves and eye protection are basic steps, but essential ones. Having spill clean-up materials, like absorbent pads and pH paper, close at hand pays off. In a real spill, time matters—and floundering for materials sets up bigger problems.

Rotating Stock and Responsible Disposal

Research moves fast, but old chemicals linger. Check every six months for powder clumping, color changes, or label damage. My team keeps a logsheet taped inside the cabinet door; we commit to reviewing it twice a year. If the acid shows odd residue or doesn't match its initial appearance, don’t risk it. Contact chemical waste handlers for approved disposal routes instead of improvising with the sink or trash bin.

Why Careful Storage Matters

The effort put into storage reflects out onto every step of experimental success. Lost purity and unexpected side products sabotage weeks of work, and careless errors can spread out and affect labmates. By devoting a little attention to storage conditions—dry, cool, protected from reactive neighbors—we honor not just the chemistry but the people and projects relying on these molecules.

What Makes Up 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid?

The backbone of many pharmaceuticals builds from benzene rings with functional groups added for activity or selectivity. In the case of 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid, two fluorine atoms attach to adjacent carbons on the ring, and an acetic acid side chain connects to the rest. Its chemical formula reads as C8H6F2O2. This formula shows eight carbon atoms, six hydrogens, two fluorines, and two oxygens in every molecule. The popular search for fluorinated groups in drug development usually connects to tweaks in bioavailability or stability. Fluorine changes the molecular landscape—making the once-familiar compounds act differently in the hands of chemists.

Crunching the Molecular Weight

Calculating molecular weight feels like a rite of passage in the lab. Every high school student with a periodic table can track each atom’s contribution. For 2,3-difluorophenylacetic acid, here’s what each set adds:

- Carbon (C): 12.01 g/mol × 8 = 96.08 g/mol

- Hydrogen (H): 1.008 g/mol × 6 = 6.048 g/mol

- Fluorine (F): 18.998 g/mol × 2 = 37.996 g/mol

- Oxygen (O): 16.00 g/mol × 2 = 32.00 g/mol

Add it together, the molecular weight rounds to about 172.13 g/mol. Having this metric matters, whether you're weighing out a sample or preparing a reaction where precise stoichiometry keeps the work honest. Most chemists know surprise outcomes appear if you ignore details like an overlooked atom or decimal.

Why Do Researchers Care About 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid?

Fluorination transforms molecules. Two fluorines in close proximity on a benzene ring can turn a benign starting material into something with punch—think altered acidity, metabolic resistance, or new routes for synthesis. Fluorinated aromatics became hot property across labs for creating next-gen drugs, imaging agents, or agrochemicals. Basic building blocks like this acid aren't just textbook examples. They slot right into pipelines for designing active drugs or probing biological systems.

Some researchers dig into these acids for their ability to introduce difluoro substitution while keeping the molecule manageable. Fluorine can jazz up a molecule’s lipophilicity or toss a wrench into an enzyme’s gearworks. This compound sometimes crops up in efforts to build selective inhibitors or to shift a compound’s absorption profile, helping candidates get past animal testing and into actual use. Experience from years in the lab says small tweaks—like two fluorines—force big changes downstream.

Challenges and Ways Forward

Chemists face real issues with sourcing and safety. Fluorinated compounds cost more to make and often break down less gracefully in the environment. Proper training with handling and disposal stands as one of the most practical needs. In academia and industry, investing in greener fluorination techniques and recycling methods can soften the impact. Collaboration among synthetic chemists, environmental scientists, and regulatory bodies helps to nudge practices away from pure output and toward responsibility. In outreach with colleagues and students, discussion often circles back to the basics: know your molecules, watch your waste, respect every step from synthesis to safe disposal. No shortcut can replace a clear understanding of what each atom in a formula brings to the table.

What it is and Why it Matters

2,3-Difluorophenylacetic acid comes up in lab work, mostly in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals or chemical research. It’s a fine example of how chemical advances shape not just medicines but also the rules around keeping chemists and the environment safe. With more specialty chemicals showing up in research and production every year, the safety questions never end.

Hazard and Toxicity Concerns

Now, the big question: are we dealing with something hazardous or toxic? Based on the chemical structure—an acetic acid group paired with a benzene ring holding two fluorine atoms—you’d expect it to be similar to other aromatic acids but possibly a little more potent because of those fluorines.

Public data is pretty limited. Nobody is handing out teaspoons of this for toxicity studies, so researchers rely on what’s known about related compounds. Aromatic acids with fluorine can irritate skin or eyes, especially in concentrated form. A lot depends on how it’s handled. Accidental exposure, especially to dust or vapors, can lead to discomfort or more severe effects like respiratory issues, which shows the need for good practices in the lab.

Standard safety documents—like the Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for similar chemicals—flag things like skin and eye irritation and possible harm if swallowed. That aligns with my time working with organic acids and halogenated compounds in university and small pharma labs: gloves, goggles, a fume hood, and common sense were always non-negotiable.

The environmental piece deserves attention. Fluorinated organic molecules tend to stick around in soil and water. Persistent pollutants make everyone’s list of worries, especially with regulations getting tighter. Nobody wants to see fluorinated chemicals build up over time.

What Science and Experience Teach Us

Dealing with new or niche chemicals means erring on the side of caution. Most organic chemists treat unknowns like potential hazards until proven otherwise. Limiting exposure, sticking close to protocols, and reviewing the latest toxicity reports helps keep things in check.

Regulatory agencies like OSHA and the European Chemicals Agency recommend assuming acute toxicity where gaps exist. I’ve seen plenty of research teams use closed systems, extra ventilation, or avoid scale-up until all the questions are answered. The cost of ignoring these steps usually shows up later in workplace injuries or expensive cleanup.

Google’s E-E-A-T framework points to trusting reliable sources and leaning on expert testimony. When reputable organizations, including academic toxicologists, don’t have a clear verdict, it’s worth paying attention. Companies investing in thorough risk assessment, improved SDS, and transparent sourcing earn more trust, especially from workers handling the material.

Safer Approaches for Labs and Factories

Every chemical comes with its risks, but training, planning, and equipment go a long way. Good habits—labeling, spill prep, and cautious handling—cut down the chance of nasty surprises. Regular disposal checks help prevent environmental release.

Industry can push for more research on intermediate chemicals instead of waiting for accidents. Partnering with regulatory bodies and universities also shortens the time from discovery to a clear safety profile.

Real safety asks for more than warnings. It demands respect for chemicals, steady education, and a willingness to ask hard questions before pouring anything into a beaker or drain. That’s how science keeps moving forward without putting people or the planet in unnecessary danger.

Why Purity Matters for 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid

Working in labs and chemical production floors, I’ve encountered a fair mix of pride and agony when it comes to raw materials. Purity sits right at the core of it all, especially with chemicals that end up in pharmaceuticals or advanced materials. 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid counts as one of those compounds that demand attention to detail, not just for performance but for regulatory and safety reasons, too. Any shortcuts, or blind spots in the QA step, and the entire batch’s reliability drops. Think of purity as the backbone of reproducibility for research and commercial syntheses.

What the Market Offers: Typical Purity Grades

Looking through catalogs and regulatory filings, most reliable suppliers of 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid put forward purity specs between 97% and 99%. You’ll find technical grade material around 97%, and high-purity grades pushing 98% or even nudging past 99% for pharma applications. Sigma-Aldrich, Alfa Aesar, and TCI mention 98% or greater for their premium products, and certificates of analysis often verify HPLC or NMR checks that back these numbers up. Anything labeled below 95% usually ends up in areas with loose specification needs or early-stage research where re-purification follows anyway.

This isn’t just about sales talk—GC-MS and NMR spectra show tight, well-defined peaks, with only trace residues from raw material, solvent, or catalyst. Impurities like related phenylacetic acids, unreacted starting material, or halide by-products fall under strict limits. Some lots even come with detailed impurity profiles—saving time and trouble once the bottle lands in the lab.

Industry Expectations and Regulatory Pressure

Few things slow down drug discovery or synthesis of advanced compounds as much as a poorly documented, low-purity batch. Regulators have grown stricter, refusing to look the other way for mislabeling or lack of traceability. Nobody in the business enjoys a surprise recall or field complaint from a downstream partner.

Companies turn to well-established suppliers who deliver tight specs, COAs, and even batch traceability, pushing sample validation and documentation to a new level. Small traders may offer cheaper material, but hidden impurities end up burning more money with extra purification or failed batches. In real terms, this means staring at HPLC traces and worrying about hidden interference peaks far more than any researcher wants.

How To Ensure Quality and Transparency

As a buyer or specifier, it pays to drill suppliers for details before placing that order. Always request a copy of the most recent certificate of analysis, showing full impurity testing by techniques like HPLC, NMR, and GC-MS. Ask if the same batch can be reserved or if retesting with a sample is possible. Direct communication with technical support teams often opens the door for granular info about the analytical methods or the source of starting materials—which often tells more about consistency than shiny brochures.

Dealing with a complex synthesis? Investing in a small validation sample makes sense before scaling up. This not only validates the stated purity for the specific application but also avoids headaches from batch-to-batch variance. Genuine high-purity products cost more than bulk technical grades, but they safeguard against lost time, failed syntheses, and compliance issues down the line.

Improving Purity and Trust in the Supply Chain

For manufacturers, tighter in-process checks and improved purification steps translate to more reliable purity. Some companies go the extra mile using recrystallization or advanced chromatography, even for medium-scale volumes. Data transparency remains crucial—suppliers who share not just numbers but also raw spectra, full impurity listings, and detailed lot info stand out in a crowded market.

Purity in chemicals like 2,3-Difluorophenylacetic Acid separates those who talk science from those who practice it. Trust gets built not by promises but by relentless documentation, independent lab checks, and honest technical answers. For every buyer who demands this, the chemical industry as a whole gets a little better, delivering results researchers and manufacturers can rely on.