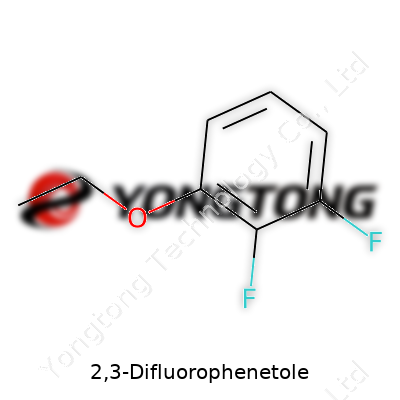

2,3-Difluorophenetole: A Comprehensive Look

Historical Development

Chemists have always pushed the barriers of precision and control in aromatic substitutions. Over the past several decades, research into substituted phenetoles illustrated that the placement of fluorine atoms on the benzene ring changes chemical behavior in subtle and big ways. In the early 20th century, simple phenetole received basic characterizations, but real curiosity ramped up after workers found out how differently fluorinated aromatics reacted in both pharmaceutical and agrochemical applications. As labs gained easier access to organofluorine reagents and milder, more selective fluorination techniques, compounds like 2,3-difluorophenetole appeared as more than curiosity—researchers started mapping their possibilities in detail, and the field kept growing.

Product Overview

2,3-Difluorophenetole stands as a clear, colorless to pale yellow liquid under ambient conditions. Its appeal doesn’t just rest on modest volatility or chemical stability—this molecule’s two closely-spaced fluorines subtly shift both the electronic nature and the reactivity of the whole aromatic ring. Unlike many other phenetole derivatives, the pairing of a fluorine duo next to each other near the ethoxy handle offers unusual stability to nucleophilic attack, all without sealing off the door to further chemical work. This balance attracts manufacturers interested in accessing building blocks for target synthesis in multiple industries.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The physical characteristics catch the eye in the lab: boiling point hovers around 181-183°C, and the density clocks in near 1.19 g/cm³. Technicians recognize the faint, characteristic ether odor during handling. The logP, often used to estimate solvent partitioning or bioavailability, demonstrates moderate hydrophobicity, falling in a range that can be useful for molecular design. The fluorines not only lower the basicity of the aromatic ring but also bring thermal and oxidative resilience, narrowing down reaction conditions for downstream work. People in the lab note the liquid’s low miscibility with water, yet it dissolves easily in organic solvents including dichloromethane, chloroform, and ethers, which makes it pretty convenient during extractions or washes.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

A supplier’s certificate for 2,3-difluorophenetole usually reports minimum assay values above 98%. Technicians keep an eye out for color (APHA below 50 is typical), refractive index matching published values, and low residue levels. On the label, you find the proper UN number, a warning for flammability, and a clear statement of storage temperature limits, usually calling for cool, dry conditions, away from oxidants. GHS-compliant pictograms for flammable liquids and possible health hazards show up on every drum. Barcode scanning for lot tracing, date of manufacture, and batch analysis make compliance and recall procedures easier for shipment in regulated environments.

Preparation Method

People in the synthesis lab learn that selective difluorination gives predictable headaches. A common way to produce 2,3-difluorophenetole involves first creating 2,3-difluorophenol by halogen exchange or direct fluorination of a suitable dihalobenzene. This intermediate then undergoes O-alkylation using ethyl bromide, ethyl iodide, or a related agent with a basic catalyst—potassium carbonate works well—under strictly anhydrous conditions. Accomplished chemists monitor the reaction by thin-layer chromatography and carry out careful distillation under reduced pressure to collect the pure ether, keeping side reactions and byproduct formation to a minimum. Improvements in fluorination agents over the years mean that modern chemists have more options and fewer hazards than their predecessors.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

2,3-Difluorophenetole opens doors for further chemistry. The ether function plays nicely with oxidation protocols, but it doesn’t tempt nucleophiles the way a methoxy or unfluorinated ring might. Direct substitution on the ring calls for strongly activating conditions—strong bases, metalation, or directed ortho/para metallation strategies—because two adjacent fluorines drop the electron density considerably. For those aiming to make functionalized aromatics, this stability might slow things down, but it pays back with cleaner reaction profiles and more selective downstream transformations, especially in cross-coupling reactions. The molecule also shows usefulness as a protected intermediate, holding off on certain reactivity until needed in a multi-step synthesis.

Synonyms & Product Names

People new to the compound sometimes see “2,3-difluoroethoxybenzene” or “2,3-difluorophenetole” on labels. CAS number 3859-59-2 often follows the name on chemical inventory systems, making ordering and compliance straightforward. Alternative trade names exist but rarely stray far from these conventions.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling any fluorinated ether requires training and respect. At ordinary temperatures, 2,3-difluorophenetole fares pretty well, but high heat or open flames turn it into a swift fire hazard. Inhalation of vapors may irritate the respiratory tract, and accidental skin contact could trigger mild dermatitis. People working with bulk amounts gear up with gloves, splash goggles, and local extraction hoods. All containers get properly earthed during transfer, because static discharges near volatile liquids have led to accidents in the past. Spill response depends on proper absorbent and containment, then disposal according to local hazardous waste protocols. Laboratories train new folks on the chemical’s specific material safety data sheet, and periodic refresher courses keep everybody alert.

Application Area

This compound’s popularity among chemists comes down to utility in custom molecule construction. In pharmaceuticals, minor tweaks to the aromatic system by adding or moving fluorines often change medicinal activity, metabolic resistance, or even selectivity at a drug’s molecular target. Agrochemical developers lean on the same logic, designing selective herbicides and pesticides that resist breakdown in soil and roots. The electronic and steric effects from a 2,3-difluoro arrangement support designers targeting new catalysts, coatings, and specialty polymers. Its robustness means the intermediate won’t give up breakdown products in harsh environments, whether in process chemistry or as a protected handle in patent-protected products.

Research & Development

Every team looking to develop new fluorinated materials faces puzzles with both synthesis and application. In the past decade, academic groups dug into structure-activity relationships built on 2,3-difluorophenetole scaffolds, discovering new routes to heterocycles, fused rings, or even fluorinated biaryls. Many startups in green chemistry now tap into milder fluorine sources and greener solvents, aiming to cut down environmental footprints. Core challenges revolve around improving atom economy, reducing byproducts, and streamlining purification. Synthetic chemists design new ligands, polymer backbones, or medical imaging agents using pieces drawn straight from this family of difluorinated ethers, hoping to unlock new properties for real-world products.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology experts caution that, even with relatively low acute toxicity in mice and rats, chronic studies haven’t been as extensive as they'd want for full confidence. Repeated exposure in animal models points to possible liver enzyme perturbation at higher doses, but clear mutagenicity and carcinogenicity flags haven’t shown up in reputable studies yet. Environmental safety teams also track breakdown products, especially from incomplete incineration: hydrofluoric acid among them, which poses a risk to both workers and downstream ecosystems. For human exposure, risk management leans heavily on minimizing vapor inhalation and skin contact, keeping air concentrations low in workspaces. Patterned after related ether and polyfluorinated aromatic studies, most safety protocols are conservative, calling for scrupulous ventilation, containment, and monitoring.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, opportunities extend far beyond traditional labs. As demand grows for high-performance materials—whether in semiconductors, protective coatings, or precision drug candidates—interest in finely tuned, stable fluorinated intermediates grows stronger. Innovation in direct functionalization promises to expand the toolbox for customizing these molecules. Regulatory trends and consumer safety expectations drive labs to gather more toxicology data, pushing for green chemistry credentials and shorter, safer synthetic routes. Emerging research into sustainable fluorination may give this compound an edge in future polymer science and pharmaceuticals. Real-world impacts only grow as more industries search for building blocks that combine chemical toughness with flexibility and low toxicity.

Tracing the Path of a Chemical Building Block

2,3-Difluorophenetole stands out in the world of specialty chemicals. Its structure, a benzene ring with two fluorine atoms and an ethoxy group, might not mean much to most people. In a lab or production plant, though, these traits help form the backbone for more complex molecules. This chemical finds a home among research teams focusing on pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and advanced materials.

Why Fluorine Makes a Difference

Adding fluorine atoms to organic compounds can be a game-changer. In drug design, small adjustments sometimes bring about big changes in how a compound interacts with the body. Compounds like 2,3-Difluorophenetole become valuable starting points for creating new drugs. I’ve seen researchers put in late nights tweaking molecules so that the right properties stick around—better absorption, improved stability, fewer unwanted side effects. Fluorinated building blocks often lie at the heart of these breakthroughs.

New Medicines Start with Small Steps

Many drug candidates begin as simple scaffolds. Chemists prefer molecules that have “handles” for further modification, and 2,3-Difluorophenetole serves that role. It can link with other structures to form antiviral, anticancer, or neurological drug lead compounds. Fluorine tweaks can make medicines last longer in the bloodstream or pass through cell walls where non-fluorinated versions would fail. According to reports from journals like Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, introducing difluorinated groups increases success rates in some pharmaceutical projects.

Agriculture Banks on Innovation

Food production also turns its eyes to innovations from chemistry. Companies study many routes toward safer, more effective crop protectants and pesticides. Molecules like 2,3-Difluorophenetole get tested as stepping stones in synthesizing new actives that shield crops from pests but break down quickly in the environment, leaving less residue.

Materials on the Molecular Frontier

Electronics and specialty polymers industries chase better performance—flexibility, heat resistance, or low electrical loss. Layering aromatic rings with fluorine can produce materials that stand up to harsh conditions where other plastics fail. Chemical manufacturers explore options, hoping these small molecules might help build the next generation of displays, sensors, or coatings. Just a few years ago, collaboration between academia and industry showed how new fluorinated intermediates increased OLED display lifespans without raising manufacturing costs.

What Could Go Wrong?

Working with fluorinated organics means handling them with respect. There’s a health and environmental cost to these useful building blocks. Persistent organic pollutants often have similar structures: strong carbon-fluorine bonds resist breaking down, persisting in ecosystems. Responsible research and transparent supply practices matter. Regulations such as REACH in Europe and inventories like TSCA in the United States push for careful tracking of substances and their impacts.

Better Science, Safer Stewardship

As a scientist, I’ve seen interest in both performance and safety rise year after year. Green chemistry initiatives push labs to cut waste and seek renewable feedstocks. Developers explore new paths that balance power with planet. Not every fluorinated molecule makes it out of the lab—many get set aside if there’s a hint of lasting harm. Progress sometimes means moving slow, testing longer, and shaping research agendas that keep public safety in mind. In my experience, that approach brings lasting benefit to industry and society.

A Look Into the Backbone

Chemistry often seems mysterious, but the foundation stays a mix of logic, shared patterns, and details that matter. 2,3-Difluorophenetole’s chemical structure offers one of those stories where tiny differences set a compound apart. This particular molecule belongs to the phenetole family, meaning it carries an oxygen atom connecting an ethyl group with a benzene ring. What makes it stand out comes down to the “di-fluoro” twist—two fluorine atoms attached strategically on the ring. Specifically, those fluorine atoms bond to the second and third positions of the benzene structure. The ethoxy group sits at the first carbon, which sets the stage for its properties and uses.

Why These Details Matter

Molecular structure deeply shapes how a substance reacts with other chemicals, behaves in different environments, and delivers benefits that scientists and manufacturers look for. Fluorine sits among the most electronegative elements on the periodic table, so dropping it onto an aromatic ring can change everything. This is the heart of chemical tuning in fields like pharmaceuticals or materials science. In practical terms, these substitutions often boost stability, tweak reactivity, and sometimes unlock entirely new applications. My background in organic synthesis proves how frustrating it gets looking for compounds that last longer or survive harsh conditions—often, just a single fluorine swap shifts the balance.

Decoding the Structure: Real World Picture

The backbone features a benzene ring, the classic six-carbon arrangement every organic chemist learns to spot even while half asleep. At the “one” spot of the ring sits the ethoxy chain—an oxygen atom bridging to an ethyl group. Moving along the ring one carbon at a time, fluorine takes up positions two and three. If you picture the molecule as a clock, with position one as noon, those fluorines take up spots about one o’clock and two o’clock. There’s nothing random about fluorine’s spots—placing them close to the ethoxy oxygen changes how electrons flow through the ring, which often tamps down unwanted reactions and keeps the molecule robust.

Applications and Importance

Fluorinated aromatic compounds see serious demand in science and industry. Their resilience in aggressive environments and strong electron-withdrawing power of fluorine often mean these molecules stick around longer and resist breakdown. Such properties make them key in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and modern materials, with each new tweak giving researchers a broader toolbox. Working on small-molecule drug design, I’ve seen even a single fluorine atom drive up metabolic stability in lab tests—a common challenge in medicine development. Fluorine not only shields the molecule but sometimes sneaks it past metabolic “gatekeepers” in the liver, meaning a drug can work longer and more efficiently.

Issues That Need Attention

While the benefits catch attention, care needs to guide how these compounds find their way into real-world use. Fluorinated arenes often prove tricky for the environment. Their stability, so prized in drug testing, means they linger when discarded. I’ve struggled with waste disposal during synthesis, since standard treatments don’t always break them down. Solutions start with lab-scale awareness—using safer solvents, capturing byproducts, and looking for biodegradable alternatives. Regulations keep catching up with these realities, placing higher standards on researchers and industries alike. Education makes a difference, too—young chemists learn the impact of every atom added, which shapes future progress toward safer and more responsible science.

Understanding the Risks

2,3-Difluorophenetole occupies a small space in the world of research chemicals, yet even small mistakes with storage can turn costly in terms of safety and reliability of results. Speaking from years spent around chemistry labs and teaching new researchers, I've seen enough incidents that remind me: chemical behavior rarely offers second chances. Liquid organofluorine compounds can surprise even seasoned chemists. Volatile compounds like this often become hazardous if left in a careless corner of the stockroom or allowed to sit in direct sunlight. Accidental spills create more than cleanup headaches — even small leaks can affect indoor air and sensitive equipment.

Room Temperature Isn’t Enough

Many people stash chemicals out of sight, thinking a cabinet is enough. I’ve learned not to trust in luck here. With 2,3-Difluorophenetole, temperature control means more than comfortable storage. Keeping the chemical below 30°C isn’t an arbitrary rule; higher temperatures raise the risk of volatilization and can let pressure build up inside poorly ventilated bottles. At worst, glass containers can fail or vent dangerous vapors. Humidity introduces another set of problems because moisture can seep in if seals aren’t tight, potentially leading to slow degradation.

Light and Air Exposure

Even with good temperature control, lighting matters. Direct sunlight, or even strong ambient light, might not fry your sample overnight, but over weeks or months, photo-degradation or discoloration can compromise both purity and yield. Opaque storage bottles shield the compound far better than clear glass. It doesn’t sound complicated, but I’ve watched well-meaning students reach for clear beakers simply because they’re handy, only to circle back months later and wonder what went wrong with their stored sample.

Choosing the Right Container

Good containers keep out air, lock out moisture, and resist attack from volatile liquids. I always recommend amber glass bottles with PTFE-lined caps for anything sensitive — not just for legal compliance, but to avoid personal headaches later. Even after all the advances in packaging, tight-fitting seals remain the first line of defense, especially against accidental evaporation. Squeeze the bottle cap and you’ll realize how vulnerable common closures feel by comparison.

Labeling and Record-Keeping

Missed or faded labels turn routine storage into a guessing game. Every bottle deserves a label with preparation date, potential hazards, and up-to-date contact information. More than once, I’ve unearthed old sample vials with only a half-legible ID number and spent far too long tracing what lay inside. Traceability counts just as much as how a sample is stored. Digital logs offer backups — they don’t fix everything, but they cut down on the lost time and risk from mishandled compounds.

Considering Hazards and Procedures

If you’re overseeing a shared storage area, make sure everyone knows the layout, the rules, and the risks. Training makes a difference — I’ve seen less experienced lab members benefit from clear guidance on the correct procedures for handling volatile or toxic chemicals. Quick access to spill kits, good ventilation, and fire safety gear in storage areas reduce both incident risk and damage if an accident does occur. And don’t forget disposal: store unused or spent 2,3-Difluorophenetole in secure waste containers, far from regular supplies, to stop unwanted reactions from lurking leftovers.

Prevention Saves Time

Over the years, I’ve found preventive habits keep everyone safer and ensure more reliable results. Tidy storage practices for 2,3-Difluorophenetole aren’t just about following rules; they save costs and trouble by minimizing waste, lost samples, and unexpected reactions. Everyone working in chemical environments deserves a culture of careful handling and respect for the substances used. That kind of environment doesn’t just happen — it comes from learning the value of preparation and diligence, and passing it along to the next set of hands reaching for the bottle.

Why Chemical Hazards Aren’t Always Obvious

Sometimes, people see a chemical name and shrug it off because it’s unfamiliar or seems disconnected from everyday life. 2,3-Difluorophenetole might not come up outside specific labs, but it’s worth giving real scrutiny. My own curiosity with chemicals began after I watched one splash out of a beaker and burn a mark into a classroom bench. Everything changed for me that day—I realized a harmless-looking clear liquid might carry hidden risks.

What Do We Know About 2,3-Difluorophenetole?

2,3-Difluorophenetole belongs to a family of aromatic ethers with two fluorine atoms attached to its ring. That might sound technical, but the main point is this: adding fluorine to organic compounds almost always changes how they behave. The pharmaceutical and agricultural industries seek out these molecules for their unique properties, but the industry also documents risks tied to similar chemicals.

As of today, detailed long-term studies on 2,3-Difluorophenetole are scarce. Most guidance comes from safety sheets and toxicity predictions that group it with compounds showing similar patterns. These analogs have been linked to skin and eye irritation, sometimes respiratory problems if inhaled, and, for some, effects on the liver with repeated exposure. With most ethers and aromatic fluorine compounds, the probability of central nervous system effects creeps up at higher exposures.

Personal Experience Shaping Attitudes about Chemical Risk

During a stint in an industrial lab, we worked with dozens of synthetic compounds, including some with close chemical cousins to 2,3-Difluorophenetole. The air always carried a faint hint of solvent, and every single spill sent us scrambling for gloves, safety showers, and extra ventilation. Even small mistakes could cause headaches or irritation. That experience stuck with me—chemicals you don’t respect have a way of reminding you who’s in charge.

Why Understanding Chemical Toxicity Matters

Ignoring potential toxicity can have long-term fallout, both at work and at home. It’s easy to think that a minor irritant doesn’t matter. Still, repeat exposure sometimes sets the stage for chronic problems. Regulatory agencies, including OSHA and the European Chemicals Agency, stress early detection and hazard labeling partly because the ugly side of many chemicals only emerges after years of routine, low-level contact. Trust in these regulations builds over time because they’re shaped by hard evidence and accumulated mishaps, not guesswork.

Making Safer Choices around 2,3-Difluorophenetole

Turning safety knowledge into habit reduces risk. My team learned to keep good records, label everything, and choose mechanical ventilation even for brief tasks. Gloves and eye protection seem basic, but that’s usually what stands between a safe lab and a trip to urgent care. Bringing up potential hazards in team meetings also shifted our work culture from one where safety rules felt burdensome to one where everyone watched out for each other.

What Needs to Happen Next

There’s a gap in public data about the environmental and human effects of 2,3-Difluorophenetole. Chemical companies and independent labs should be pushed for more transparency and testing, sharing insights into acute and chronic toxicity. Greater awareness in research circles, beyond just those handling the molecule, gives society a better shot at balancing valuable innovation against unwanted harm.

Pushing for Quality in Research Chemicals

Anyone digging into synthetic chemistry has probably come across the topic of reagent purity. It isn’t just a matter of splitting hairs. A few tenths of a percent in either direction sometimes change the way a whole research project unfolds. 2,3-Difluorophenetole is no exception. This compound shows up in all sorts of pharmaceutical research and agrochemical experiments. The finer details count.

Packing In the Purity Details

I’ve watched many labs jump through hoops to get their hands on starting materials with a purity over 98%. In some cases, even 99% doesn’t quite satisfy a persnickety process — you want one contaminant in a reaction, not a soup. For 2,3-Difluorophenetole, top manufacturers almost always offer purities of at least 98%. This gives researchers confidence that side products won’t hijack their reactions.

Companies routinely test their lots by gas chromatography or NMR, and that level of transparency shapes who gets business. I’ve seen folks request full certificates of analysis, demanding nearly forensic evidence the bottle contains what it claims. Extra purification pushes the price up, but most scientists see it as money well spent if it means clean results. In my experience, the headache of chasing down ghost peaks in your data isn’t worth a cheaper but dirtier option.

Flexible Packaging for Lab and Industry

Package sizing also says a lot about how a chemical gets used. A small medicinal chemistry group working on novel molecules might only want 1 gram, maybe a 5-gram bottle. I’ve ordered tiny vials before, especially during early lead discovery work — safer, less waste, and you’re not paying for more than needed.

On the flip side, once a project scales, everyone starts talking in bottles, then in kilograms. A pilot plant or scale-up division needs bigger packs, and vendors respond with choices like 25-gram, 100-gram, or even 500-gram bottles. Larger drums up to 25 kilograms appear for industrial settings. These big sizes come with extra considerations around safety, labeling, and transport. Picture a glass bottle in a foam-lined box, capped tight, sometimes with desiccant packs to keep out moisture.

Why Packaging and Purity Go Together

A lot of trouble crops up if packaging can’t keep up with high purity levels. I’ve seen oxidation ruin a batch because of a poorly-sealed cap. Fragile glass breaks in shipping, and you’re out both time and budget. Suppliers who take packaging seriously — sometimes double-sealed containers, or nitrogen purged vials — become partner material, not just a nameless entity.

I’ve watched labs return products because a seal broke in transit, and then all QC bets were off. A partnership forms based on trust in each container arriving the way it should: labeled, undisturbed, and well-documented. The right bottle size means less decanting and less exposure to air, which protects your investment.

Looking Forward

Getting the basics right with 2,3-Difluorophenetole, from high purity to reasonable package size, helps keep research bold and reproducible. Open communication between vendor and researcher smooths out bumps before work even starts. Solid documentation, careful packing, and purity checks matter as much as anything on a reaction scheme. After all, nobody built good chemistry on the back of old mistakes or shoddy supply lines.