An In-Depth Commentary on 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic Acid: Science, Safety, and the Road Ahead

Historical Development

Fluorinated benzoic acids emerged on the scientific stage in the late twentieth century, tracing their roots to a time when researchers sought to expand the range of building blocks in organic synthesis. 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid didn’t arrive as a star from day one. Its rise began as chemists realized that selectively adding fluorine atoms onto the benzene ring could tweak chemical properties in useful ways. Through the years, refining synthetic methods meant that greater purity and larger quantities became an every-year reality. I’ve seen the buzz around fluorinated compounds shift from niche curiosity to integral roles in medicinal chemistry, agrochemicals, and advanced materials, reflecting a hunger for molecules with new levels of stability and unique reactivities.

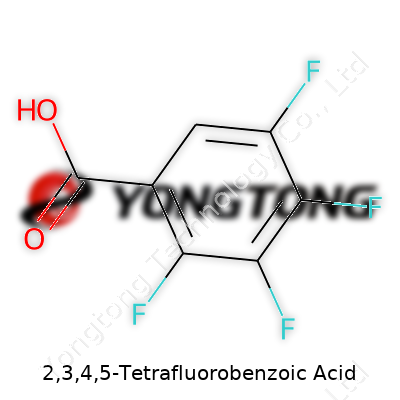

Product Overview

At its core, 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid stands as a solid organic acid boasting four fluorine atoms arrayed across the benzene structure. Most suppliers offer it in crystalline or powder form, and it typically arrives in amber glass bottles to shield the substance from light exposure. Each batch arrives with a certificate of analysis, listing key purity markers, absence of critical impurities, and spectroscopic signatures. Reliable sources back quality with transparent documentation, which matters whether someone works in academic synthesis, pharmaceutical innovation, or specialty chemical production.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Looking at the bench, this acid shows up as a white to off-white powder, thanks to its dense packing and aromatic backbone. The melting point falls somewhere between 155-158°C, which helps in purification and quality control by recrystallization. In terms of solubility, it dissolves in most organic solvents like dichloromethane and dimethyl sulfoxide, but water solubility tends to drop off because of the hydrophobic aromatic ring and the strong electron-withdrawing effect from the fluorine atoms. The acid dissociation constant (pKa) is much lower than non-fluorinated benzoic acids, making it a stronger acid, another reason it earns its place on the synthesis bench. I remember one project where its acidity and reactivity saved three synthetic steps, just by avoiding the need for activating agents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labeling matters in labs and on the plant floor. Each vial or drum clearly marks the compound name, its Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) number (cas 61060-31-5), clear hazard statements, batch data, and expiration date. Purity typically impresses, with high-performance liquid chromatography confirming 97% or better for research uses, and 99% batches offered for applications where side products risk derailing sensitive reactions. The safety data sheet arrives glued with up-to-date handling directions, toxicology data, and legal transport info, following GHS standards set by regulatory bodies like OSHA or REACH.

Preparation Method

No compound like this falls from the sky. The mainstream method starts with tetrafluorinated precursors. Direct oxidation of 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorotoluene using potassium permanganate or chromic acid offers one of the most practical lab-scale routes. Laboratories equipped for aromatic halogenation sometimes make the precursor through sequential fluorination steps, using agents like Selectfluor or DAST. Scale-up faces challenges — managing exothermic reactions and the production of hazardous by-products — but diligent control over temperature, stirring, and gas venting keeps synthetic routes reproducible and safe. Each step marches forward, propelled by decades of technical learning and periodic tweaks that ramp up yield or improve crystallinity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

What gives this acid value in a synthetic chemist’s toolbox is its ability to engage in transformations where the aromatic system’s electronics change game rules. The acid group welcomes amidation and esterification, producing intermediates for drug design. Meanwhile, the fluorines dial down nucleophilic aromatic substitution from the ring, making direct substitutions rare, but open doors for metal-catalyzed couplings. One research team I followed used Suzuki couplings to introduce even more complex groups, building scaffolds for agrochemical trials. Hydrolysis of esters, decarboxylation under heat, reductions, and more can be tailored by controlling reaction conditions. Chemical versatility like this, especially when combined with the chemical inertia of the fluorinated ring, turns a humble white powder into a springboard for next-generation molecules.

Synonyms & Product Names

Suppliers and researchers often call this compound by more than one label. The most usual synonym remains 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid, but it pops up in catalogs as Benzoic acid, tetrafluoro-, or TFB acid. Some proprietary names exist depending on the supplier, and academic papers sometimes use chemical shorthand like TFBA. This can trip up searchers if they chase literature or purchase requests, so double-checking registry numbers pays off every time.

Safety & Operational Standards

Every workspace handling this acid must respect its irritant classification. I always reach for lab coat and nitrile gloves before the vial comes out, since direct skin or eye contact leaves a lasting sting. Good ventilation removes airborne particles, and I keep an eyewash nearby given the mild corrosivity on mucous membranes. Storage rests best in cool, dry spaces away from acids, bases, or oxidizers to reduce risk of accidental mixing. Disposal follows local hazardous waste requirements, especially because fluorinated by-products can outlast a lot in soil or water. Emergency training and written standard operating procedures mean no one gets careless just because this acid might seem routine.

Application Area

This molecule finds home across much of synthetic chemistry, but most excitement comes from medicinal and materials research. In pharmaceuticals, adding tetrafluorinated groups enhances drug stability, slows metabolism, and tweaks bioactivity, an approach big companies adopt to turn good leads into longer-lasting medicines. Agrochemical manufacturers value similar properties for crafting agents that survive sun and rain. In the world of advanced polymers, this acid seeds fluorinated backbones that shine in coatings, membranes, and specialty plastics resisting heat or chemical attack. Analytical chemistry picks up on the molecule as a standard for instrument calibration and trace fluorine testing. Lifetime exposure to these fields convinces me that no other group of atoms amplifies molecular properties quite like a simple swap for fluorine.

Research & Development

Academic and industrial teams continue mining 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid for new tricks. Current R&D buzz tracks how it helps generate biologically active small molecules, especially candidates for enzyme inhibition or receptor modulation. Some projects tackle more sustainable synthesis, developing greener oxidants or continuous-flow reactors that cut toxic waste. On the analytical side, researchers explore novel uses as a tag for mass spectrometry. Fluorinated benzoic acids, including this one, also serve as radiolabel precursors in PET imaging, a game-changer in diagnostics. Funding cycles and publication booms suggest interest isn’t waning — if anything, fresh ideas pop up with every new grant call and patent application.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology studies paint a cautious picture. The parent acid displays low acute oral and dermal toxicity in animal models, but repeated or chronic exposure can inflame skin, eyes, or respiratory tissues. A few studies flag potential bioaccumulation issues with related fluorinated compounds, urging careful control of industrial effluents and routine biomonitoring in workplaces. Well-run labs and factories invest in personal exposure testing and environmental audits to head off surprises down the line. Regulators push for longer-term studies tracking low-level, chronic contacts in human populations, which may take years to complete but could reshape future guidelines just as it happened with their perfluorinated cousins.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the market for specialized fluorinated aromatics grows in step with demand for longer-lasting, tougher, and safer molecules in health, agriculture, and electronics. Improvements in synthesis — harnessing electrochemistry, biocatalysis, or more selective fluorination tools — promise to lower costs and expand supply chains. Watch for new functionalized analogs branching out from 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid to appear as patented intermediates and active ingredients. Stricter environmental and safety rules will shape everything from manufacturing design to labeling, keeping both hazards and compliance front and center. As researchers probe molecular effects deeper, applications will keep expanding, from smart textiles to tailored sensors and therapies. The story of 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid reads as a pulsing signal of fluorine’s influence on tomorrow’s science and industry.

Bringing Chemistry Out of the Shadows

Labs and factories buzz with all sorts of chemical names, but 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid really grabs the curiosity of anyone who’s peered at a reagent shelf. Some chemicals get plenty of attention in popular science stories, but fluorinated benzoic acids like this one do much of their work in the background, pushing progress without fanfare.

What Drives Researchers and Companies to Use It?

Pharmaceutical teams often look to 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid for new molecule design. Adding fluorine atoms usually helps drug candidates slip across cell membranes, which can mean pills work better or reach the right spot in the body. Sometimes just one extra fluorine changes how fast a medicine breaks down or where it travels in the body. These tweaks help manage side effects and boost the results both patients and companies want.

People involved in agrochemicals don’t ignore this acid either. Modern pesticides and herbicides need to stay working out in the field but break down safely later. Dropping fluorine onto a molecule often changes its persistence in soil or water. That kind of tailoring helps products work just long enough before nature breaks them down. Farms in my region have seen a few of these new designs appearing in sprays, thanks to breakthroughs from the lab benches of specialty chemical teams.

Building Blocks Beyond Medicine and Agriculture

What your average hardware store stocks might not run on 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid, but electronics and materials science are a different story. I’ve met researchers who push for better polymers—those tough, lightweight plastics in electronics insulation or medical devices. By adding small acid groups like this one, scientists build up polymers that last longer and handle higher voltages, and sometimes even repel water and oil. These plastics end up in connectors, wire jacketing, and high-end circuit boards—places where a crack or short circuit means wasted money or real danger.

Chemical catalogs also showcase this acid as a handy intermediate. If you want to build up a bigger or fancier molecule, you sometimes tack on this building block, fiddle with it, then clip it off again or swap out those fluorines for something else. Labs in the energy storage sector use these kinds of tricks to tune battery chemicals for better safety or faster charging, and I’ve seen patent filings crediting tetrafluorinated rings as key steps.

Keeping Safety and Environment in Mind

As with all fluorinated chemicals, the story isn’t free from concerns. Some fluorinated compounds have landed public health and environmental agencies in the news, with worries about how long they stick around after use. Regulators keep a careful eye on solvents and intermediates, wanting to avoid the repeat of “forever chemicals.” Good research practice and tighter tracking help teams spot trouble before it builds up. Responsible disposal, recycling, and greener process design matter as much as fast-paced innovation.

Teaching new chemists, clarity and transparency always come up. Chemical producers need to make data on toxicity and breakdown part of their labels and safety sheets. There’s a growing push for better databases that help small labs and global manufacturers see which compounds present low risk, and which call for more training or special gear.

Better Living with Careful Chemistry

Each year, uses for targeted fluorinated acids grow. Whether it’s better pain relief, safer pest control, or tougher electronics, the ultimate benefit hinges on respect for both science and safety. For those who care about what’s next—whether on the farm, in the clinic, or atop the lab bench—that’s worth keeping an eye on.

Understanding the Basics: Fluorinated Compounds in Everyday Life

Many people reading the label on a specialty chemical feel a sense of mystery. Names can seem long and intimidating, but there’s value in breaking things down. The chemical formula for 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid is C7H2F4O2. Looking at this simple string of letters and numbers, most would not realize just how carefully chemists fine-tune molecules to get desired properties.

Dissecting the Formula: Where Science and Pragmatism Meet

2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid is a derivative of benzoic acid, where four hydrogen atoms on the benzene ring have been replaced by fluorine atoms at the 2, 3, 4, and 5 positions. Replacing hydrogen with fluorine on aromatic rings happens for a reason. Fluorine is smaller than most halogens, highly electronegative, and far from passive in chemical behavior. Adding it to organic molecules changes how these molecules interact, both with each other and with the world around them.

Having handled chemicals with fluorine groups, I know production settings demand reliable performance. Tetrafluorobenzoic acid serves as a building block for more complex pharmaceuticals, specialty polymers, and agrochemicals. Its structure lets it participate in reactions that standard benzoic acid cannot. The formula C7H2F4O2 means four positions are now highly resistant to unwanted reactions, improving stability and reducing breakdown during synthesis.

Real-World Impact: Research, Industry, and Safety

Fluorinated benzoic acids like C7H2F4O2 crop up in industries beyond academic labs. I’ve seen colleagues in environmental testing use them as reference standards when tracking pollution from fluorinated compounds—especially since fluorine atoms stay in the environment for a long time. Their unique signature makes them easy to trace, which matters for assessments of water quality and food safety. No other class of organics leaves quite such a distinct fingerprint in mass spectrometry.

This advantage becomes a double-edged sword. Fluorinated organics resist breakdown, which gives value in pharmaceuticals and electronics. At the same time, persistence raises concerns about bioaccumulation and environmental toxicity. The industry faces questions: Can manufacturers design molecules that serve a function without leaving a problematic legacy? Restricting unnecessary use, improving degradation pathways, and researching greener synthetic routes all deserve attention. Even when making small tweaks—like swapping a single fluorine for another substituent—chemists weigh stability, toxicity, and cost, not just theoretical properties.

Solutions and Responsible Innovation

Companies investing in sustainable chemistry look for ways to recover and recycle fluorinated waste. A few have set up take-back programs for unused chemicals, which don’t just protect the environment, but help labs manage storage and disposal. Academic researchers investigate catalytic systems that break down these acids safely. Small advances win trust—especially as regulatory scrutiny of persistent pollutants ramps up. A clear, well-labeled bottle of C7H2F4O2 means more than a chemical; it demands honest communication about risk, utility, and stewardship.

Fluorinated benzoic acids might seem niche on paper, but the details—such as its formula C7H2F4O2—carry ripple effects across industry, research, and safety policy. As someone who’s worked with these compounds, the bigger lesson is clear: in chemistry, every atom added or removed has purpose, and every formula deserves both respect and responsibility.

What 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic Acid Is All About

Ask any chemist about 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid, and you’ll find it’s a mouthful both in name and in structure. This compound belongs to a family of fluorinated benzoic acids, often popping up in the lab for synthesizing specialty chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and advanced materials. Because it’s not an everyday household item, there’s plenty of confusion about the risks it may bring.

The Reality Behind Its Toxicity

People tend to assume that anything with “fluoro” in the name must be highly dangerous. That’s not always true, but fluorine in organic compounds does change the game. Fluorinated aromatics like this one often show persistence in the environment. I’ve worked in labs where we never treated any fluorinated compound as harmless—even minor exposure was always a reason to check safety sheets and reach for the gloves.

Reliable databases, including the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and PubChem, lack detailed public toxicity data for 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid. That’s rarely a good thing—it usually means researchers haven’t published enough animal studies to qualify its risk. For reference, similar compounds in the group sometimes cause eye and skin irritation on contact. Inhalation of fine dust from benzoic acid derivatives causes respiratory issues in sensitive folks. Nobody wants a cough or rash over something that could have been prevented with common-sense precautions.

Potential Environmental Impact

Personal experience shows that chemists don’t take chances with persistent chemicals. Fluorinated aromatics like tetrafluorobenzoic acid have stability under harsh conditions, and that’s part of their industrial appeal. But it also means they can hang around in soil and water, building up over years. Research on similar fluorinated compounds, such as polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), reveals a troubling pattern: these molecules don’t break down easily, and they sometimes slip into groundwater. Studies have linked long-term exposure to some perfluorinated acids with immune, reproductive, and carcinogenic effects in animals and possibly humans.

We don’t need to reach for sensational headlines to see why waste management matters here. If a fluorinated compound ends up in the water supply, cleaning it up gets tricky. Municipal treatment plants usually can’t break down stable fluorinated rings, leaving communities at risk of low-level, ongoing chemical exposure.

Balancing Lab Safety and Industry Progress

In academic labs, whenever a new or unusual fluorinated aromatic comes into play, the unwritten rule goes: always read the MSDS, treat it as a potential risk, and avoid unnecessary exposure. Even without proven high-level toxicity, the unknowns keep most chemists on their toes. We rarely underestimate the value of good gloves, fume hoods, and proper disposal habits.

Industry-wide, the answer isn’t to shy away from useful chemistry. Instead, responsible companies invest in employee training, modern ventilation, and regular environmental checks. Countries leading the push for safer chemical handling—like Germany, Sweden, Japan—make publicly available data a must. If manufacturers and researchers keep sharing toxicity and environmental data, the public’s trust goes up. So does industry safety.

Moving Toward Smarter Chemical Use

The importance of well-documented research on chemicals like 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid can't be overstated. Governments and companies that require registration, evaluation, and greater transparency help prevent unwanted accidents or contamination. With advanced testing and more openness, the science community and the world around it both benefit.

A Practical Look at Chemical Storage

Getting storage right for specialty chemicals makes a real difference—not just for safety, but for product lifespan and lab credibility. You never want to find your materials degraded after months on a forgotten shelf. I’ve seen that with complex reagents and it always means wasted money and extra headaches. 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid falls into the group of chemicals that demand extra respect around storage.

Why Conditions Matter

Organic acids with several fluorine atoms bring a mix of stability and reactivity. The fluorines help limit moisture uptake, but there’s no guarantee against slow hydrolysis or other changes, especially if a container sits open in a warm, damp storeroom. Walk in many academic or industry labs and you’ll see how easy it is to skip even basic things like screw cap tightness—then containers crust up or product gets clumpy.

For those of us trained in laboratory practice, maintaining a dry, cool environment always stands out. 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid responds poorly to high humidity and fluctuating temperatures. Moisture and heat cause discoloration, changes in potency, and even safety complications.

Setting Up a Storage Plan

Secure a dedicated chemical cabinet for organics. Even in spaces with limited resources, a simple steel or plastic cupboard away from sunlight keeps temperature stable. Use containers with tight seals—preferably glass with PTFE-lined caps—since some resin plastics react over months or let low-level vapors pass through.

Choose a spot out of direct heat sources, far from radiators or sunlight through a window. If the label suggests a specific refrigeration temperature, follow it. I’ve worked with many specialty acids that kept properties for years just by sitting in a fridge at 4°C. Make sure there’s a desiccator inside or silica packets taped to the container. Moisture sneaks in surprisingly fast, especially in climates with seasonal dampness.

Never put these kinds of chemicals near bases or reactive metals. Even accidental cross-contamination from poorly wiped glassware or a nearby leaky vessel can start unpredictable reactions. Once, a shared shelf meant an accidental spill of alkali near a benzoic derivative, causing dangerous fumes and ruined product.

Label Clearly and Record Details

Paying attention to labels saves more than frustration later; it’s a habit from professional chemical handling that really pays off. Write out the date, any special precautions, and storage temperature directly on the bottle. Back this up with a digital log, so if someone else checks or moves the container, no vital information gets lost. I’ve audited labs where inconsistent labeling led to errors, lost batches, and even compliance risks with inspections.

Reliable Practice Builds Credibility

Manufacturers point out that strong stewardship—proper storage, up-to-date documentation, clear labeling—sets apart reliable labs from amateurs. That’s not just compliance, but also a matter of keeping staff and spaces safe. By treating 2,3,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzoic acid with a cautious approach, you avoid breakdowns, preserve quality, and earn trust with your results. Investing a bit of time into careful storage each time pays back by keeping valuable chemicals ready and steady on the shelf.

Working with Fluorinated Aromatics

Dealing with heavily fluorinated benzoic acids always calls for patience and some creativity. In academic labs and industrial settings, 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid shows up in medicinal chemistry routes, agrochemical research, and polymer building blocks. Strong carbon-fluorine bonds and the unpredictability of multiple fluorine atoms squatting on the same ring turn each synthetic attempt into a test of skill and persistence. Methods keep improving, but the chemistry rarely feels straightforward.

Direct Oxidation of Precursors

Starting from 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorotoluene still ranks as one of the more practical methods. Oxidizing this methyl group to a carboxylic acid can involve classic potassium permanganate oxidation or a milder catalytic system with air or oxygen. In my hands, permanganate in basic water works well for small batches but tends to choke up with dark manganese wastes, making work-up rough. Copper- or cobalt-catalyzed aerobic oxidations look attractive for the scaling crowd—greener, less gunky waste, but usually longer wait times and more precise control needed.

Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Strategies

Sometimes, you have to build your aromatic system stepwise. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution, taking something like pentafluorobenzene as a starting point, lets folks swap out a fluorine for a group that can be pushed further toward a carboxylic acid. Typical chemistry here uses potassium or sodium cyanide—the cyano group takes a position, then gets hydrolyzed under acidic or basic conditions to finish the acid. Handling cyanides always raises eyebrows for safety and environmental reasons; labs put strict protocols in place, and you learn to respect the risks.

Halogen Exchange and Lithiation Routes

For those who like a bit of flash with their chemistry, halogen-lithium exchange delivers a quick route to functionally substituted rings. You can start from a halogenated tetrafluorobenzene, throw in a strong base like n-butyllithium at low temperature, and quench with carbon dioxide to install the acid. The cooling, the flashing solvents, and the need for dry, oxygen-free setups scare off some, but once you get the rhythm of the technique, it can be satisfying and highly selective. In these steps, every glovebox or Schlenk line mishap sticks with you longer than the faint smell of ether.

Evolving Methods and the Push Toward Sustainability

Green chemistry pressures shape choices in labs worldwide. Even old-school chemists agree the relentless use of toxic metals, harsh oxidants, and dangerous reagents invites regulation and waste headaches. Flow chemistry and electrochemical approaches, though still gaining traction, could help shift these syntheses into safer, cleaner territory—passing reactants through a small reactor limits personal exposure and waste. Researchers have started harnessing electrosynthesis for direct carboxylation, minimizing reagent loads.

Why Method Selection Matters

Each approach offers a different balance. Yield, waste production, setup complexity, and cost all factor in. For me, choosing the path to 2,3,4,5-tetrafluorobenzoic acid always means thinking about the end use—if I need only a gram, an old-school batch process feels sensible. For scale-up, the only sensible way forward involves robust, cleaner, and safer methods. The real challenge isn’t just getting fluorine in place; it’s making sure the process doesn’t trip up on cost or green chemistry concerns down the line.