1,2-Difluorobenzene: A Detailed Look at its Journey, Uses, and Future

Historical Development

The path to understanding 1,2-difluorobenzene reveals how ingenuity and curiosity move science and industry forward. Chemists in the early twentieth century began exploring benzene derivatives, experimenting with fluorination methods that at first gave mixed results. The creation of 1,2-difluorobenzene was not accidental—real advances in handling hazardous fluorine and mapping substitution patterns brought it to life. Early reports in research journals from the 1940s and 1950s show small-scale syntheses and detailed studies on how to control fluorination, given the element’s stubborn reactivity. Key advancements in electrophilic aromatic substitution and later, catalytic and direct fluorination techniques, led to the reliable production of this compound. As the demand for specialized aromatic chemicals increased in the latter half of the century—mainly for agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals—producers refined the process, enhancing both yield and safety.

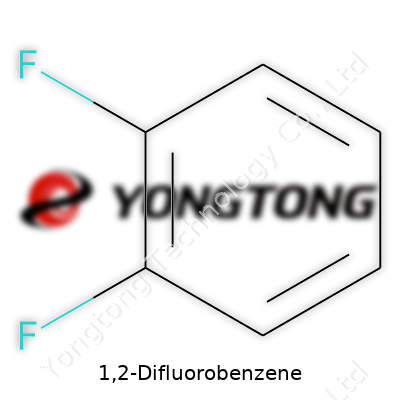

Product Overview

1,2-Difluorobenzene has become a staple in chemical research and fine chemical manufacturing. Its structure—two fluorine atoms attached to adjacent positions on a benzene ring—offers chemists a valuable handle for designing molecules with distinct electronic and physical properties. Modern commercial samples often appear as clear, colorless liquids. Companies selling it to laboratories and manufacturers highlight its usefulness as a solvent, intermediate, or reference material, owing to robust stability and pleasant inertness under many reaction conditions. The chemical’s existence in high purity enables precise reproducibility in both analytical and synthetic work.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This molecule, C6H4F2, boils at 90–93°C and melts around -41°C, making storage and handling straightforward under typical conditions. The density hovers near 1.16 g/cm3. Those two fluorine atoms pull electron density from the benzene ring, which gives the compound a slightly higher polarity than regular benzene yet keeps it hydrophobic and only faintly soluble in water. It dissolves easily in organic solvents like hexane, ether, and dichloromethane. Physical appearances may not set it apart instantly, but its relatively low vapor pressure and moderate toxicity require care in larger operations.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Chemists and suppliers insist on quality metrics. Technical sheets for 1,2-difluorobenzene list assay values, usually above 99%, and clearly outline permitted levels for water, acids, and related fluorobenzenes. Containers typically display the CAS number 367-11-3, alongside hazard pictograms: the compound earns the exclamation mark for skin and eye irritation risk. Barcodes and lot numbers let users track each batch’s origin. Because small impurities can compromise experimental outcomes, especially in pharmaceutical research or high-throughput screening, producers document every analytical result—as well as storage warnings to keep away from moisture and open flames.

Preparation Method

For years, the go-to method relied on direct fluorination of o-dichlorobenzene or difluorination of benzene itself, with antimony trifluoride and chlorine as key reagents. Modern techniques frequently swap out these older, sometimes hazardous approaches for more selective catalytic systems. Palladium- or copper-catalyzed reactions offer better yields and allow a degree of tunability. Electrochemical fluorination and specialized fluorinating agents like Selectfluor or DAST have pushed bench chemists to new levels of control, reducing side products and environmental hazards. Most large producers have switched away from the harshest reagents, but academic labs still draw on classic textbooks for small-batch recipes.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

1,2-Difluorobenzene’s versatility comes from the interplay of its aromatic system and the electron-withdrawing influence of fluorine. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution lets chemists swap out fluorine for amines, alkoxides, or other groups, especially under heat or in the presence of catalysts. Its stability under many acidic and oxidizing conditions makes it a reliable backbone for further modifications. In cross-coupling reactions like Suzuki or Heck processes, the molecule acts as a foundation for constructing more complex architectures—a boon for anyone assembling pharmaceuticals or advanced materials. Reactions with organometallics or via hydrogenation unlock even more pathways, giving researchers a toolkit for tailored design.

Synonyms & Product Names

Buyers and researchers might encounter several names for this chemical: o-difluorobenzene, ortho-difluorobenzene, and benzene, 1,2-difluoro-. Sometimes catalogues abbreviate it simply as 1,2-DFB. On product labels, you may see synonyms listed to prevent confusion during international or cross-supplier communication. The CAS number offers the most reliable way to identify the substance, especially when translation or local naming conventions shift.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety demands respect in every lab or factory that uses 1,2-difluorobenzene. Inhalation or absorption through the skin can cause irritation or worse, so experienced chemists rely on fume hoods, gloves, and eye protection as the norm. Spills, though not likely to spark violent reactions under most conditions, call for swift containment with inert absorbents. Larger installations keep integrated gas detection systems on hand to monitor low-level fumes. Clean air and regular training help limit the risk of chronic exposure, while up-to-date safety data sheets ensure every user stays informed about potential reproductive hazards and regulatory guidelines. Strict waste procedures—neutralization and secure destruction—reduce the environmental burden.

Application Area

My own work in research has shown just how wide the reach of 1,2-difluorobenzene stretches. As a solvent, it dissolves both ionic and lipophilic reactants with an efficiency that standard solvents cannot always match—especially in NMR spectroscopy, where low background signals help reveal subtle information. The compound takes center stage as a building block for agrochemicals and active pharmaceutical ingredients, offering unique pharmacokinetics and chemical stability. In material science, its stable ring and reactive sites allow design of new polymers, particularly when tuning dielectric properties for electronic use. Custom synthesis teams often rely on it for tricky substitution patterns that older benzenes fail to support, pushing boundaries in dye chemistry and advanced coatings.

Research & Development

Current R&D efforts dig deeper into the selective activation of the C–F bond, an area where traditional methods fell short. Teams working in catalysis labs are charting how transition metal complexes can break and reform these bonds, creating even more intricate molecules. Analytical chemists have found new ways to exploit the molecule’s strong NMR signals, designing probes for environmental and biological tracking. Interest continues to grow in sustainable synthesis, with researchers pursuing methods that cut greenhouse gas emissions and waste products. I have watched colleagues test continuous flow methods and automation—technologies that transform both safety and throughput for custom manufacturers.

Toxicity Research

Studies into toxicity show moderate acute effects in animal tests, mostly respiratory and skin irritation. Unlike some simpler aromatic hydrocarbons, the presence of fluorine reduces the rate of metabolic breakdown, which can leave traces in tissue for longer periods. Regulatory bodies in Europe and North America track environmental persistence and the possibility of long-term hazards—especially in the event of spills. Extensive monitoring studies have yet to turn up hard evidence of severe chronic toxicity in humans under typical handling, but industrial hygiene guidelines err on the side of caution, enforcing exposure limits well below those for some other aromatic solvents. My experience with safety audits tells me that periodic reviews keep these limits up-to-date as more studies roll in.

Future Prospects

Future opportunities for 1,2-difluorobenzene seem bright, especially in energy and pharmaceutical innovation. As companies seek high-performance battery electrolytes or next-generation electronic materials, unique properties emerge from fine-tuning aromatic fluorination patterns. Growing demand for selective fluorination in drug design promises more work for chemists mastering this tricky chemistry. Improved manufacturing processes, including greener catalysts and real-time quality monitoring, will likely curb environmental impacts and boost production yields. I believe that ongoing collaboration between academic groups and industry specialists will open new doors for safer applications, smarter synthesis, and wider use in global markets.

The Chemistry Behind the Name

Ask a chemist about 1,2-difluorobenzene, and chances are you’ll hear its formula: C6H4F2. This formula tells the backbone of the molecule—six carbons, four hydrogens, and two fluorines. It’s more than just letters and numbers on a page. Knowing it gives a peek into how this compound behaves. It helps predict things such as boiling point, solubility, and even how toxic or stable it might be. Each part of the formula stands for a distinct role the atoms play in shaping the chemical’s character.

Everyday Relevance and Real Risks

Some might ask why regular folks should care about such a formula. Chemicals like 1,2-difluorobenzene show up behind the scenes in electronics, specialty solvents, and even some pharmaceutical syntheses. The formula is like a name tag—it keeps chemists and safety officers from mixing up lookalikes. Miss out on one hydrogen or toss in another fluorine, and the whole safety sheet flips. Fluorine isn’t just any ordinary atom; it can make substances far more volatile or harder to break down. As someone who once watched a university lab scramble when a bottle was mislabeled, I’ve seen how crucial it is to keep these formulas straight.

Behind the Letters: Health and the Planet

Tinkering with benzene rings and fluorine leads to chemicals that don’t always play nice with the environment. If you get the formula wrong, environmental predictions and cleanup plans go off track. C6H4F2 breaks down differently than its close cousins. The chemical structure shapes its persistence in soil and water, as well as its impact on living creatures. Agencies like the EPA set standards by looking closely at the details described by these formulas. In the age of green chemistry, picking the right compound for the job depends on knowing these seemingly simple combinations inside out.

Handling and Regulation

Judging by the formula, professionals get a good sense of how to store and handle a chemical. 1,2-difluorobenzene, with its two fluorines, asks for different precautions than regular benzene. Proper labeling keeps workers safe and regulators satisfied. Incorrect chemical identification ends up costing money, health, and sometimes lives, especially if a mix-up leads to overflow, spill, or chemical reaction. Students training in labs often learn this lesson fast—whether from textbooks or, more often, from the sharp scent after a fume hood blunder.

Supporting Decision-Making and Innovation

1,2-difluorobenzene continues to matter as chemists invent new materials. The formula offers clues about how to swap atoms in and out, helping design safer, more effective compounds. Those working on replacing harmful solvents use information tied directly to these arrangements. For decision-makers, formulas like C6H4F2 act as guideposts, reducing trial and error and focusing attention on known risks and proven techniques. Sharing such knowledge openly helps students, industry experts, and regulators aim for a safer, smarter world.

The Role in Chemical Research

Anyone who has worked in a chemistry lab probably recognizes 1,2-difluorobenzene from the shelf of specialty solvents. This compound comes into play most often as a solvent in reactions involving tough materials like metal complexes or strong bases, where standard solvents like water or ether just can’t get the job done. I’ve worked with enough stubborn organometallic compounds to appreciate what a difference solvent choice makes. The two fluorine atoms on the benzene ring give this liquid a unique mix of properties — it’s polar, but not so reactive that it ruins sensitive materials. For chemists trying to coax a reaction to completion or keep a delicate intermediate stable, being able to reach for a bottle of 1,2-difluorobenzene changes everything.

Tuning Electronic Materials

Advances in electronics often hinge on new chemical methods. Scientists looking for ways to assemble tiny circuits or flexible displays often turn to unusual aromatic solvents. 1,2-difluorobenzene can dissolve organic semiconductors and metal-containing dyes that other liquids simply can’t hold. In my experience, this makes it a staple in labs pushing OLED displays and printable electronics beyond yesterday’s limits. Its boiling point lets delicate molecules stay in solution without breaking down, so researchers get more value from the raw materials. Over the past decade, these experiments have fueled brighter, longer-lasting LED panels and more efficient solar cells, which are changing how people power homes and gadgets.

Pharmaceutical and Agrochemical Building Blocks

A molecule like 1,2-difluorobenzene doesn’t just serve as a solvent — it’s a useful starting point for synthesizing new materials. Fluorine atoms make pharmaceuticals more stable and change how they behave in the body. Many modern drug molecules include small amounts of fluorine, and difluorinated aromatics often show up in the blueprints for antivirals, cancer drugs, and enzyme inhibitors. Labs regularly use 1,2-difluorobenzene as a core to build more complicated drug scaffolds. The same logic drives its use in crop science, where it adds weather resistance or boosts the performance of pesticides. We see this every time a new, longer-lasting treatment enters the market.

Managing Risks and Looking Forward

The benefits of 1,2-difluorobenzene also raise red flags. Fluorinated chemicals have come under scrutiny because some linger in soil and water long after their intended use. Experience tells me that safety protocols and waste disposal standards help minimize harm, but not every lab around the world follows best practices. One solution comes from process chemistry — using smaller amounts through continuous flow reactors, instead of big-batch processes that pump out more waste. Another path focuses on greener alternatives that mimic difluorobenzene’s strengths without sticking around forever. New regulations already push chemical producers to rethink what they make and how they sell it. The science keeps evolving, and smart policies can help ensure valuable molecules like 1,2-difluorobenzene remain instruments of progress without creating lasting problems.

References :

- “Fluorinated Aromatic Compounds: Applications in Materials and Pharmaceuticals,” Chemical Reviews, 2021

- “Green Chemistry and Fluorinated Solvents: Opportunities and Challenges,” Green Chemistry, 2020

- OECD Global Portal to Information on Chemical Substances

Taking Chemical Hazards Seriously

Working around chemicals strengthens respect for safety. 1,2-Difluorobenzene seems unassuming as a colorless liquid, even smells sweet, but it’s anything but harmless. Its vapors sting the nose and throat, and a single splash on skin can cause irritation. Those clear, almost gentle chemicals like this one often teach the hardest lessons if care slips.

Keeping It Off Your Skin and Out of Your Lungs

I always reach for gloves before touching any aromatic solvent. Nitrile stands up best against 1,2-Difluorobenzene. Latex won’t cut it. The moment gloves look thin or show any sign of softening, swap for new ones. Eyes need cover too. Safety goggles should fit snugly—nothing less when sudden splashes can burn eyes or impair sight.

Breathing in its fumes feels unpleasant and can damage health. I never trust extraction systems automatically; every fume hood gets tested for flow. Slow fans or a cracked sash risk exposure, so a quick check with a small tissue confirms the draft. Respirators come into play for bigger spills or breakdowns, not daily use, but knowing how to seal one onto your face matters just as much as proper use of gloves.

Labeling and Storing: No Half-Measures

One lesson I learned early: never use mystery bottles or old labels. Each container for 1,2-Difluorobenzene gets a clear, chemical-resistant label. No guessing, no rushing. Storing this solvent with incompatible stuff, like oxidizers or open flames, can end in disaster. Keep it away from heat, sunlight, and anything that sparks. Metal cabinets with good ventilation cut down risk, and spill trays offer backup in case a bottle tips over.

Spills and Waste: The Fast Response Counts

Even the best-prepared lab spills something sooner or later. The trick is acting fast, not panicking. Spill kits stocked with absorbent pads, gloves, and waste bags sit in easy reach. If 1,2-Difluorobenzene splashes out, absorb the liquid right away, scoop up solids, and seal everything in marked waste containers. Larger spills mean evacuating the area and calling in hazmat support.

Waste storage needs its own care. Wait until containers are almost full before sealing them tight—don’t overfill. Both liquid and contaminated solids head to hazardous waste pickup, not the drain or regular trash. Keeping detailed waste logs and tracking volumes avoids nasty surprises during inspections.

Training: The Overlooked Essential

Written rules and checklists only go so far. Real understanding comes through practice and short drills. Walking through real-life scenarios—like a bottle breaking or a glove ripping—closes the gap between theory and readiness. Empowering team members to speak up about odd smells or missing labels, without fear of blame, helps spot dangers early.

Why Vigilance Matters

Years spent with solvents like 1,2-Difluorobenzene show that slack routines breed close calls. Trusting your senses, using proper gear every time, and keeping procedures sharp—these habits prevent accidents and keep everyone healthier in the long run. Blind faith in luck, shortcuts, or blurry labels almost always leads to regret. Genuine care creates safety where it counts: in each small choice, every day.

Temperature Talks: 1,2-Difluorobenzene and the Boiling Point

Not every day brings up the need to check the boiling point of something like 1,2-difluorobenzene. Still, sometimes these details make all the difference, especially in a laboratory or manufacturing setting. For the chemists out there, that sharp 90.1°C (194.2°F) boiling point can turn into a big deal. That number doesn’t just show up in textbooks for fun; it underpins safe handling, storage, and even the cost of working with the stuff.

Why Knowing the Boiling Point Is More Than Academic

I still remember handling solvents in a university lab, where missing the mark by even a couple of degrees could lead to ruined experiments or, worse, a room full of fumes. Small molecules behave differently above or below their boiling range. 1,2-difluorobenzene boils at a temperature a bit under water’s boiling mark. It means the vapor pressure ramps up faster than you might expect. If someone left the cap off a bottle, that lab bench turned into a nose-stinging mess. Safety issues aren’t theoretical; they walk right into the room with each open bottle.

The toxicity of aromatic fluorinated compounds demands attention. Fumes are more than just an inconvenience; they bring health risks. Breathing them in, especially in poorly ventilated spaces, can irritate airways and seem to trigger headaches. Proper ventilation and fume hoods save the day, but nothing helps if workers don’t recognize the flashpoint between liquid and vapor. That’s where the boiling point informs daily routines: scheduling distillations, choosing storage temperatures, or even deciding how far a bottle can safely travel from cold storage to the workbench.

Cost, Risk, and Reliability in Industrial Settings

Industries banking on consistency rely on the boiling point during chemical synthesis and purification. Overheating a reaction, even by small increments, can change yield outcomes or send costs skyward. The 90.1°C mark plays into decisions involving distillation efficiency and separation steps. Every extra degree uses more energy and chews through budgets. Prices of fluorinated solvents aren’t dropping, so knowing where and when those liquids change phase protects the bottom line.

Supporting the Facts

Science isn’t about gut feelings. The boiling point of 1,2-difluorobenzene stands on published data from sources like PubChem, the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, and actual industry reports. A lot of process engineers strap digital sensors on glassware, double-checking that temperature mark to avoid costly mistakes. Researchers working with derivatives often use this boiling point as a reference in analytical techniques, calling out contamination if samples budge off the chart during gas chromatography.

Ways to Reduce Hazards and Stay Efficient

In my lab days, strict labeling, closed storage, and real training mattered way more than a sticker on a bottle. It helps to rely on audited safety data sheets and refresher courses for everyone who might handle organic solvents. Automated systems with digital temperature monitoring can flag problems before they escalate. In bigger facilities, linking storage temperature controls to alarms shaves down accidents, keeping everything within the safe zone below the boiling mark.

Smart handling ties right back to the facts: 1,2-difluorobenzene boils at 90.1°C. Understanding this one number supports safer workspaces, sharper process control, and better bottom lines. Science, money, and safety all come together over one small line in the handbook.

What is 1,2-Difluorobenzene?

1,2-Difluorobenzene belongs to a family of chemicals that show up in labs and industrial settings. Chemists rely on it to dissolve tough substances and carry out reactions that other solvents just can't handle. Its oily consistency and strong smell make it easy to spot in the lab. Many folks outside of chemistry spaces may never hear about it, but if it goes down the drain or spills during transport, its story changes.

Health Concerns That Stand Out

Breathing in or coming into contact with 1,2-difluorobenzene isn't something most people do every day. For chemists who handle this stuff, it's a different deal. Its vapors get into the air fast, especially if you're not using a fume hood or working in a closed system. People who've worked with similar chemicals often talk about headaches, nausea, or dizziness if the fumes build up. Skin contact causes irritation. Repeated exposure, especially through inhalation, could knock liver or kidney function off balance based on animal research.

In my own years around these labs, gloves and goggles turn into non-negotiable must-haves. Coworkers who once thought skipping protection was okay often learned the hard way: red skin, irritated eyes, or worse. Reading safety sheets can feel like a drag, but one misstep gives you a lesson you won't forget. Allergic reactions or serious poisoning rarely happen, yet they make safety culture essential wherever this chemical shows up.

What About Environmental Impact?

Chemicals in this family tend to stick around in the environment if they escape from labs or factories. 1,2-Difluorobenzene doesn't break down quickly in water or soil. This means that a small spill becomes a big deal if it seeps into groundwater or rivers. Fish and other aquatic life don’t handle this chemical well; studies show higher concentrations harm them or even wipe out populations in test tanks. Plants growing in contaminated dirt take up these compounds, which then move up the food chain.

One time I worked at a site where a leak ran into a small ditch. It turned into a headache for weeks: dead tadpoles, a persistent chemical odor, and a cleanup bill that nobody liked seeing. Moments like that push more companies to invest in tight storage and better monitoring. You see that environmental mistakes rarely stay hidden—they impact local communities, wildlife, and reputations.

Practical Solutions for Safer Handling

Responsible use takes solid training. Employees working with 1,2-Difluorobenzene need real-world instruction, not just a packet of safety guidelines they check off. Fume hoods, sealed containers, and regular checks make up the baseline for safety. Labs that stick to these protocols see fewer accidents and less unexpected exposure. Disposal matters just as much—neutralization steps keep this chemical from showing up in sewage or landfill sites where it has no business being.

Regulators weigh in, too. Limits on airborne concentration and proper labeling protect not just workers, but first responders who might stumble across this stuff in a fire or leak. Community right-to-know efforts help neighbors understand what’s nearby, building trust and letting people speak up if storage or disposal looks sloppy.

Why Diligence Matters

Every hazardous chemical—1,2-difluorobenzene included—calls for a tough mix of respect, caution, and open communication. Relying on good ventilation, proper storage, and up-to-date training pays off. When I think back on days spent cleaning up small spills or helping new lab techs gear up before a long shift, it’s clear that small steps keep bigger problems away. Staying vigilant and following best practices doesn’t just keep workers safe—it protects soil, water, and everyone living nearby.